One of the largest ever studies of how climate change is remaking the face of the Arctic has found that shrubs are gradually taking over the tundra.

And David Hik, co-author of the paper in Nature Climate Change, said the increasing dominance of shrubs over grasses is likely to be the cause of its own climate feedback.

"The shrubs are a dark surface and they reflect less of the sun's radiation back into the atmosphere," he said.

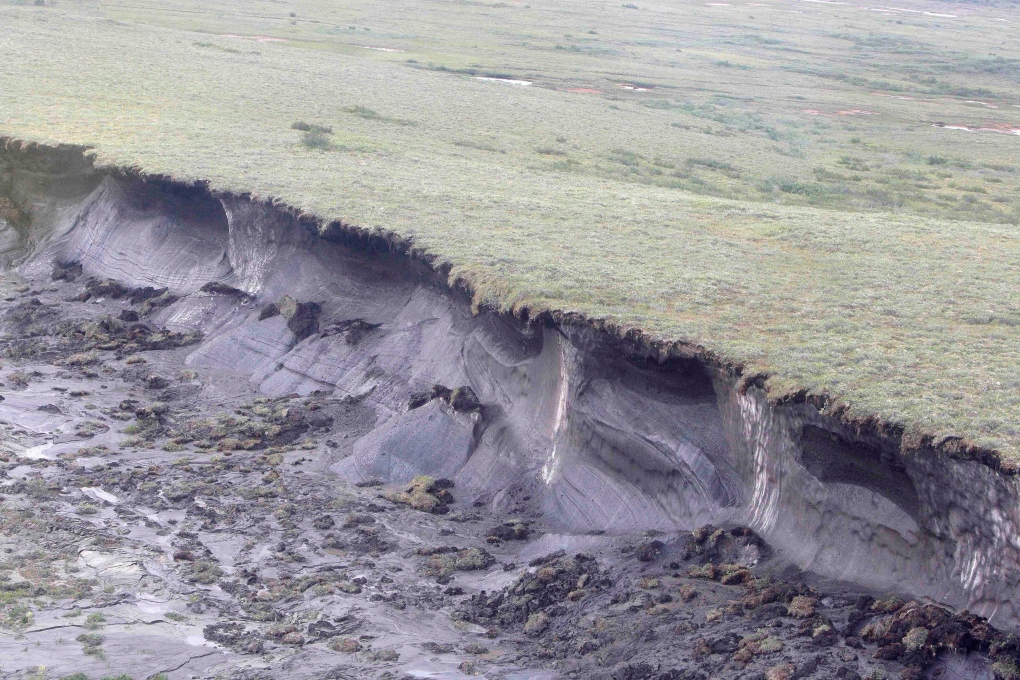

Shrub roots, which penetrate deeper into the soil than grass roots, are also likely to break up permafrost and allow water to trickle down into it.

"All of the evidence is that that leads to the release of stored carbon into the atmosphere," Hik said.

Hik and his colleagues completed a study that looked across nine Arctic countries and used data collected over 60 years. Although scientists have known for some time that shrubs were gradually moving north, the rate at which the "shrubline" is moving in different parts of the Arctic has been a mystery.

Hik's paper suggests the changes are happening faster in northern Europe and Russia than they are in North America. They also found that soil moisture and depth are crucial factors in how fast shrubs expand their range.

The slow shift from grassy to shrubby landscapes could have profound consequences for the people and animals that live there.

Caribou, for example, require the lichens found in the open tundra and can't eat shrubs. Moose, on the other hand, love to browse on shrubs and their population has been growing in the North.

As well, Arctic permafrost is considered one of the globe's great storehouses of greenhouse gases such as methane, which is much more potent in its climate-changing effects than carbon dioxide.

Studies such as this, which collect and digest data from vast areas of the globe, are the future of climate science, said Hik.

"We're now putting all of our data together and trying to understand what's happening at a larger scale."