Testing a person’s blood for a type of protein called phosphorylated tau, or p-tau, could be used to screen for Alzheimer’s disease with “high accuracy,” even before symptoms begin to show, a new study suggests.

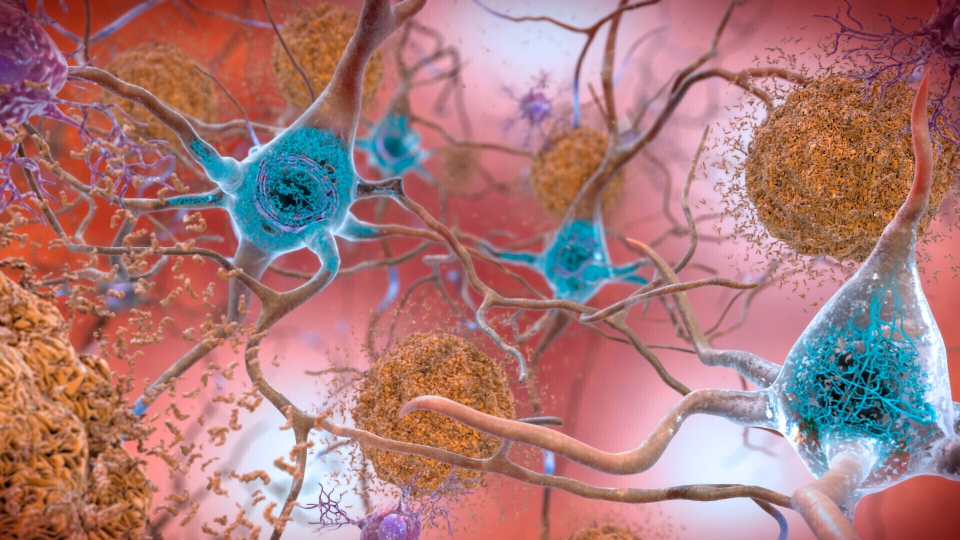

The study involved testing blood for a key biomarker of Alzheimer’s called p-tau217, which increases at the same time as other damaging proteins — beta amyloid and tau — build up in the brains of people with the disease. Currently, to identify the buildup of beta amyloid and tau in the brain, patients undergo a brain scan or spinal tap, which often can be inaccessible and costly.

But this simple blood test was found to be up to 96 per cent accurate in identifying elevated levels of beta amyloid and up to 97 per cent accurate in identifying tau, according to the study published Monday in the journal JAMA Neurology.

“What was impressive with these results is that the blood test was just as accurate as advanced testing like cerebrospinal fluid tests and brain scans at showing Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the brain,” Nicholas Ashton, a professor of neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden and one of the study’s lead authors, said in an email.

The study findings came as no surprise to Ashton, who added that the scientific community has known for several years that using blood tests to measure tau or other biomarkers has the potential to assess Alzheimer’s disease risk.

“Now we are close to these tests being prime-time and this study shows that,” he said. Alzheimer’s disease, a brain disorder that affects memory and thinking skills, is the most common type of dementia, according to the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

Last year, the first blood test for assessing beta amyloid protein was made available for consumer purchase in the United States, called AD-Detect, to help people with mild cognitive impairment identify their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Some researchers have raised doubts about the science behind the test. Quest Diagnostics, the company behind the test, has stressed that it is not meant to diagnose Alzheimer’s, but says it helps assess a person’s risk of developing the disease.

The test used in the new study, called the ALZpath pTau217 assay, is a commercially available tool developed by the company ALZpath, which provided materials for the study at no cost. The test is currently available for research use only, but Ashton said it is expected to be available for clinical use soon.

“This is an instrumental finding in blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s, paving the way for the clinical use of the ALZpath pTau 217 assay,” Professors Kaj Blennow and Henrik Zetterberg from the University of Gothenburg, co-authors of the study, said in a press release. “This robust assay is already used in multiple labs around the globe.”

ALZpath estimates the price of the test could be between US$200 and US$500.

“A robust and accurate blood-based biomarker would enable a more comprehensive assessment of cognitive impairment in settings where advanced testing is limited,” the researchers wrote in their study. “Therefore, use of a blood biomarker is intended to enhance an early and precise AD diagnosis, leading to improved patient management and, ultimately, timely access to disease-modifying therapies.”

For instance, the test demonstrated “high accuracy” in identifying tau pathology within people who tested positive for beta amyloid, according to the study. That may help guide treatment decisions in patients considering therapies that target beta amyloid, such as Leqembi and Aduhelm, since they may be less effective in patients with advanced tau pathology, the researchers wrote.

“These results emphasize the important role of plasma p-tau217 as an initial screening tool in the management of cognitive impairment by underlining those who may benefit from antiamyloid immunotherapies,” the researchers wrote.

Blood test ‘definitive’ in 80 per cent of participants

The study included data on 786 people, who had an average age of 66 and had brain scans and spinal taps completed, as well as blood samples collected. The data and those samples came from the Translational Biomarkers in Aging and Dementia, Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention and Sant Pau Initiative on Neurodegeneration.

Some of the participants showed signs of cognitive decline while undergoing the data collection but others did not. The researchers, from institutions in Sweden, the United States and other countries, analyzed the participants’ data from February to June of last year.

The researchers found that when they tested a participant’s blood sample with the p-tau217 immunoassay, the blood test showed similar results and accuracies in identifying abnormal beta amyloid and tau as the results from the participant’s spinal tap or brain scan.

Only about 20 per cent of the study participants had blood test results that, in a clinical setting, would have required further testing with imaging or a spinal tap due to being unclear.

“This is a significant reduction in costly and high-demand examinations,” Ashton said in the email. Therefore, based on the study findings, “we think that a blood test and clinical examination can have definitive decision in 80 per cent” of those who are being investigated for early signs of dementia.

Yet even though the blood test in this study was found to be highly accurate in predicting whether someone has key characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease in their brain, not everyone with those characteristics will go on to develop the disease.

Also, the p-tau test is specific for Alzheimer’s disease, so if someone tests negative but is showing signs of cognitive impairment, this test could not determine other possible causes of their symptoms, such as vascular dementia or Lewy body dementia.

“A blood test being negative speeds up the investigation for other causes of the symptoms and this is just as important,” Ashton said.

Overall, a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease, such as the one described in the new study, can be used to help diagnose both a person experiencing early memory loss, as well as before a patient shows signs or symptoms of the disease, because changes in the brain can occur about 20 years before the onset of overt symptoms, said preventive neurologist Dr. Richard Isaacson, director of research at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Florida, who was not involved in the study.

“This is actually the test that has, at this time, among the best available evidence for being one single test for Alzheimer’s,” Isaacson said about the study’s findings. “This study takes us one really powerful step closer to having that test, and the beauty of this study is it also looked at people before they had symptoms.”

Signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease can vary from one person to another, but often memory problems are the first signs of the disease, such as losing track of dates, getting lost, misplacing things or having difficulty completing tasks, such as bathing, reading or writing.

Isaacson, who has researched blood biomarkers in people with no or minimal cognitive complaints, likened testing blood samples for signs of Alzheimer’s disease to how people undergo routine blood tests for high cholesterol.

“People get cholesterol tests before they have a heart attack. People get cholesterol tests before they have a stroke. To me, this type of test will eventually be best served in people before they start to have cognitive symptoms,” Isaacson said. And “just like cholesterol tests, by following the pTau217 level over time, we can better understand how various therapies and lifestyle changes are working to keep Alzheimer’s under better control.”

A way to help ‘democratize access’

Testing for Alzheimer’s before someone has symptoms “leaves a lot of time” for that person to make brain-healthy choices and to talk to their doctor about their individual risk factors, Isaacson said, adding that a blood-based test also can be more cost-effective than performing brain scans or other methods of testing.

“PET scans have radiation and can cost over US$5,000. Spinal taps are great because you get detailed information, but not everyone wants one and it is expensive and not covered by insurance. These blood tests are generally more reasonably priced,” Isaacson said.

“Having a blood test like this can also help democratize access for people and just make it easier for our health care system to more proactively manage the tsunami of dementia risk that our society is facing,” he said. “This is the key to unlock the door into the field of Alzheimer’s prevention and preventive neurology.”

More than 6 million people in the United States are living with dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, and the number of people affected is projected to double in the next two decades, rising to some 13 million in 2050.

In the future, adults older than 50 may be recommended to undergo routine blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease, said David Curtis, honorary professor at the University College London, who was not involved in the new study.

“When effective treatments to prevent the progression of Alzheimer’s disease become available it will be essential to be able to identify people who are at high risk before they begin to deteriorate. This study shows that a simple blood test might be able to do this by measuring levels of tau protein in the blood which has been phosphorylated in a specific way. This could potentially have huge implications,” Curtis said in a statement distributed by the UK-based Science Media Centre.

“Everybody over 50 could be routinely screened every few years, in much the same way as they are now screened for high cholesterol. It is possible that currently available treatments for Alzheimer’s disease would work better in those diagnosed early in this way,” he said. “However, I think the real hope is that better treatments can also be developed. The combination of a simple screening test with an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease would have a dramatic impact for individuals and for society.”