Archeologists re-examining a trove of objects from a Bronze Age burial mound in the Caucasus first excavated in the 19th century believe that decorated gold and silver tubes were not sceptres or canopy supports as first thought, but are actually the world’s oldest known drinking straws.

The burial mound, also called a kurgan, at Maikop was first excavated by Professor Nikolai Veselovsky of St. Petersburg University in 1897 and swiftly became famous for its rich burial and extensive cultural artifacts. The kurgan contained a large chamber divided into three differently-sized compartments, each with the remains of an adult in a crouched position.

The main compartment contained what the archeologists posit was the most important individual as it was furnished with the most luxurious set of funerary offerings.

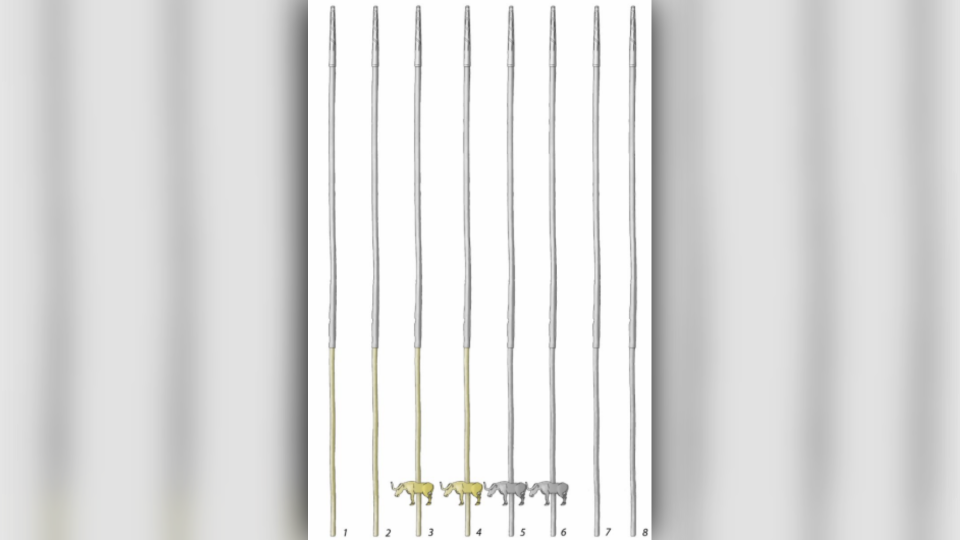

The skeleton was covered in the remains of a rich garment, with hundreds of beads of semi-precious stones and gold, and the compartment was full of grave goods – including a set of eight long, thin gold and silver tubes, four of which were decorated with a small gold or silver bull figurine.

Veselovsky at the time referred to them as “sceptres” as they were placed at the right-hand area of the skeleton.

The entirety of the Maikop kurgan was transferred to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and was presented to the Tsar’s family and special guests at the annual exhibition of the Imperial Archeological Commission.

However, new analysis of the trove at Maikop argues that the “sceptres” were drinking implements, discussed in a recent study in the journal Antiquity.

The study notes the craftsmanship of the tubes, which have sliding and movable parts made out of separate thin gold and silver segments that were soldered together.

The archeologists argue in the new study that the advanced design of the tubes was for sipping a type of beverage that required filtration during consumption.

Researchers arrived at that theory by looking at the historical record of evidence for drinking beer in the “Sumerian” style, which pre-dates the Caucasus find by centuries, and is associated with drinking beer through long tubes, as seen from seal impressions found in northern Iraq and western Iran, and on a rock-cut panel in Kurdistan.

The common ancient Sumerian method for drinking beer was to use a tube made of a long reed, which allowed the user to sit or even stand and drink from large vessels positioned on a low pedestal.

A reed decorated in gold foil found in a grave for Queen Puabi in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, the ancient Sumerian city-state located in modern-day Iraq, is the example used by the study to understand the process of making a tip filter for a drinking tube from either a reed or in the case of the Maikop kurgan, metal.

In order to test their theories, the researchers analysed a small sample of the residue from the inner surface of one of the eight filters found in the Maikop tubes, which revealed remnants of barley starch, cereals and pollen from a lime tree.

The study argues that further analysis will need to be done to rule out cross-contamination of the tubes but that if they are correct, the Maikop kurgan is the site of the earliest known drinking straws. The discovery would also suggest long-distance contact between the northern Caucasus and the Near East.