Canadian scientists say they've tested a unique one-two punch to treat patients with a deadly form of brain cancer, finding that in a small subset of patients, it stopped their tumour from growing or eliminated it.

The study, published in the journal Nature, reports the overall survival rate among the 49 glioblastoma patients treated in Canada and the U.S. was about 12.5 months – longer than the average six- to eight-month lifespan for patients with glioblastomas that return despite aggressive treatment.

"We have a 50 per cent overall increased survival, which is remarkable. It's almost double what an individual person would have lived," said study lead author Dr. Gelareh Zadeh, a neurosurgeon and co-director of the Krembril Brain Institute at the University Health Network in Toronto.

Most intriguing, say researchers, is that six patients saw their tumours shrink by at least 50 per cent on an MRI scan. Survival in this small group was also much longer. Some lived 40 months or 48 months, and two patients had complete remissions and are still alive. Zadeh says one man in Canada is still doing well 69 months (nearly six years) after the experimental treatment.

"If he wasn't my own patient, I would have really had a hard time believing that this result is true, but he's living he's well, " said Zadeh, who is also a physician at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

"His MRI brain scans remain completely disease free," she said in an interview with CTV News.

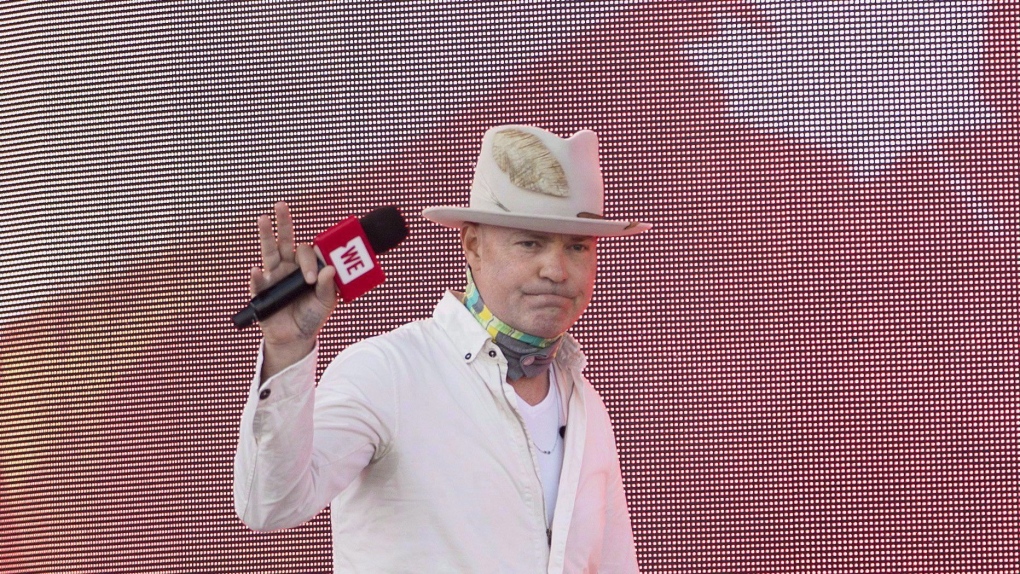

Glioblastomas have been among the most dreaded cancers because even after the initial tumour is removed with surgery, followed by radiation and chemotherapy, cancer usually returns seven or eight months later. There is no established treatment after that, making glioblastomas fatal. It's the same cancer that took the life of Canadian singer-songwriter Gord Downie in 2017.

The experimental therapy was tested on 49 patients with glioblastomas that had recurred between 2017 and 2019 at 15 hospitals in the U.S. and one in Canada.

Researchers first injected a modified cold virus directly into the patient's brain tumour through a small hole in the skull. The virus (called DNX-2401, or oncolytic virus) is engineered to infect glioblastoma cancer cells and kill them. The treatment also causes an inflammatory reaction in the cancer cells that remain.

A week later, patients began receiving IV infusions of a cancer immunotherapy drug. Pembrolizumab is an anti-PD1 drug, part of a new class of medications that rev up the patient's immune system. That allows the patient's immune cells to better find and kill cancer cells. Because of the viral infection, doctors say, more of the cancer cells are now likely visible to the immune system because of the treatment-induced inflammation.

"So it's really a kind of a paradigm shift for us, and the way that we treat brain tumors," said Dr. Farshad Nassiri, a senior neurosurgery resident at the Krembil Brain Institute at UHN.

"It's really the first time where we're now taking a therapy that's novel at part of surgery and combining it with a second therapy that's novel outside of surgery after surgery is completed," he added.

The study reports that the combination was safe, and had no unexpected side effects.

"Seeing some of our patients alive three-plus years after treatment is something that we previously would have never thought or imagined to be possible," said Nassiri.

NEW GENETIC BIOMARKER

Researchers also report they discovered for the first time that patients with recurrent glioblastomas have three genetic types when it comes to responding to this immune combination therapy, which Zadeh described as "hot, cold or intermediate immune markers."

After performing genetic tests on tumour samples, scientists found that all six of the patients who improved had the intermediate type, suggesting this biomarker, if validated with more study, may help doctors decide who might benefit from the novel combination treatment.

"It's the first time that we've just demonstrated different immune subtypes of a glioblastoma that has a complete direct bearing on response to this treatment," said Zadeh.

"It was a well-done study," wrote Dr. Lorne Brandes, in an email. Brandes is an oncologist from Winnipeg who reviewed the study for CTV News.

"The overall survival of about 12 months was longer than average in a population of recurrent disease."

But he added a note of caution because scientists don't yet know how this combination therapy compares to other treatments.

"The findings remind me of the previous studies injecting gliomas with the polio virus under similar circumstances," wrote Brandes in an email.

"Initial enthusiasm was high, as there were two or three patients who had remarkable complete remissions. This quickly led to larger studies which largely ended in disappointment."

Still, those who speak for patients say they are encouraged to hear of this new approach that goes beyond chemotherapy and radiation.

"We haven't seen a breakthrough in almost two decades, we welcome this advancement," said Angela Scalisi, chairperson of Brain Cancer Canada.

About 1,000 Canadians are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year and 95 per cent die within the first few years.

Researchers meanwhile say there are discussions underway among several medical groups for another study.

"I think there's reason to be hopeful, but without question, the next steps would be to do head-to-head comparisons to other treatments," said Nasiri.