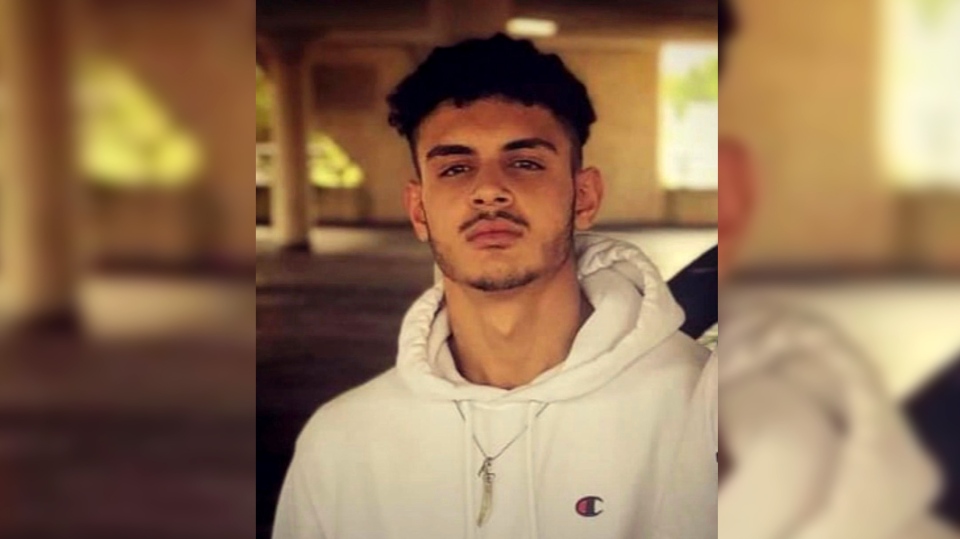

TORONTO -- The death of Yassin Dabeh, a former Syrian refugee who died from COVID-19, is a sign of the “human rights catastrophe” facing newcomers and migrants working on the front lines, advocates say.

The 19-year-old died last week and had worked at Middlesex Terrace Limited long-term care home in Delaware, Ont., which is dealing with a virus outbreak. His family had sought refuge in Canada in 2016 after moving from Syria.

“Yassin dreamed of starting a new life, getting a job, having a future and proper education,” his father, Ahmad, said Tuesday at a virtual press conference. He described his son as a “sweet, lovable boy” who was “very caring.”

Both of Yassin's parents and several members of his immediate family also contracted COVID-19, which meant they could not attend his burial. Yassin's mother was in hospital three times, but is now recovering at home.

Long-term care homes and farms are two of the biggest sources of COVID-19 outbreaks and deaths in Canada, with worker advocates noting that these low-wage, precarious jobs tend to be filled with racialized people, migrants and newcomers, like Dabeh.

“This young man came to Canada with his family with the hopes of having a better life,” Syed Hussan, executive director for advocacy group Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, told CTVNews.ca over the phone.

“Canada promised his family and other migrants and refugees that this was a better place. And we can see that if you’re a low-wage worker or a racialized migrant, that’s not true.”

Hussan noted most migrants and some newcomers don’t have access to employment insurance or other recovery benefits, so they often have to make a choice between staying home sick and paying the bills or getting a paycheque but risking infecting others.

“People don’t have any savings, so when they’re being faced with these immense challenges with COVID, they’re forced to keep working in sub-standard and dangerous conditions,” he said.

“We call this a human rights catastrophe,” Hussan said, arguing that “only the most privileged in our society seem to be the most protected.”

NEWCOMERS, MIGRANTS 'HAVE A LOT OF FEAR AND WORRY'

Last year, Majd Yared caught COVID-19 from his wife, who worked at a Lethbridge, Alta. daycare. Early on in the pandemic, the late Marcelin François, who was a personal support worker at the Montreal long-term care home, died of the disease. Yared, François, and Dabeh had all only moved to the country within the last five years.

A report from the left-leaning Broadbent Institute outlined issues facing racialized groups including, “personal care workers forced to work shifts at multiple long-term care homes… [and] migrant farm workers living in abysmal conditions with little to no access to basic workers’ rights.”

“The COVID pandemic has really shone the light better on the conditions under which they work,” Stephen Kaduuli, a refugee rights policy analyst for advocacy group Citizens for Public Justice, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

He isn’t surprised by the disproportionate effect on certain groups, who he says are “risking their lives with this essential work… that Canadians do not want to do”

Kaduuli explained newcomers and migrants working on construction sites, migrant farms, and in long-term care homes “have a lot of fear and worry” because they often live in small, cramped spaces, where they can’t physically distance from family members or roommates.

“It is very terrifying to think that you left your country to come to Canada and then you end up doing this precarious front-line work and somebody ends up dead,” Kaduuli said. But not having paid sick leave or consistent hours can take an additional toll.

“I think it sends many of them into great depression, it sends some of them to alcohol, and in some cases, we see mental breakdowns.”

'WE'RE SUPERHEROES… UNTIL WE TALK ABOUT RIGHTS'

He said it should be a rude awakening “for those who’ve always been against immigration,” to see the sheer amount of immigrants, newcomers and migrants helping on the front lines in long-term care homes or on farms.

“Newcomers are very resilient people,” Kaduuli said. “The newcomers take these jobs so they can look after the people they left back home in [places such as] Africa, Asia, Latin America. They do not come here for welfare. People do not come here to offload their problems in Canada. They come here to find a better life.”

Early on in the pandemic, entire neighbourhoods were prone to banging pots and pans for front-line workers but advocates say now is the time to fight for newcomers and migrants on the front lines too.

“We’re superheroes, or we’re all essential, until we talk about rights. It’s fine to bang pots and pans but they’re [not] paid sick days,” said Hussan, who works to improve working conditions for migrants and newcomers.

He said Migrant Workers Alliance for Change has pleaded with all levels of government for supports such as paid sick days and a ban on evictions, arguing “the lack of support for migrant, racialized low-wage workers has resulted in immense suffering.”

But there has been resistance to paid sick days. Last week, Ontario Premier Doug Ford said there’s “no reason” for the province to introduce its own paid sick leave program, even amid mounting criticism from advocates who say that an existing federal program doesn’t do enough to protect workers.

Kaduuli said private companies and temporary work agencies “need to give them a better work environment,” which includes long-term solutions such as higher-paying jobs, so workers aren’t forced to juggle multiple jobs and potentially expose themselves or their families to the virus.

But part of the solution is giving strong assurances that front-line migrants and newcomers will have a clearer pathway to permanent residency, said Hussan, who fights for workers in this situation.

“If you speak up about a bad job, you’re liable to be kicked out of the country,” he said, calling it “an added disadvantage.” He said what will go a long way is ensuring employment isn’t so tied to whether undocumented migrants can stay in the country.

Protestors make a human clock during an action in support of migrant worker rights in front of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, in Toronto, on Sunday, Aug., 23, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christopher Katsarov

Being a permanent resident didn’t spare Dabeh from contracting the virus, but Hussan said putting up these protections would still be impactful to the roughly 1.6 million migrants who are working similar jobs.

Kaduuli said the federal government also needs to better “recognize the competencies of newcomers.” Part of that “giving a better deal” to newcomers means accepting accreditation they gained in their home countries -- something other groups have also flagged.

“We want them to go back to level one, so that they ‘start off fresh’ but they have to pay bills. So they end up doing precarious work,” he said.

Hussan agreed, saying migrants and newcomers “sustain society, we’re the ones who are the construction workers, the cleaners, the delivery workers, the health-care workers, the security guards -- and we’re the ones who are bearing the brunt of the crisis. And not being able to actually survive. ”

As to whether governments and companies will listen, Hussan said “we don’t have, frankly, any time to lose. We are living in daily crises… so we can’t wait until after the pandemic.”

Kaduuli said he only knew “we have a lot of work to do and that the [advocacy] work must continue. We have to keep pushing, so that there’s recognition on the part that has been played by newcomers.”