A Toronto woman says she was charged more than $1,000 to access her deceased father’s electronic medical records, claiming the hospital changed its fee policy and backdated it to a day before she sent in her request.

In August 2018, Iris Kulbatski’s father died at the age of 74 after his prostate cancer spread to other areas of his body. The death came as a shock to Kulbatski and her family because they believed he had been living cancer free since 2011 when he underwent surgery to have his prostate removed.

During his biannual checkups at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre from 2011 to 2017, Kulbatski said her father was consistently given the all clear from his doctor. In 2016, he underwent a CT scan to look for a cancer recurrence, but Kulbatski said they were told it turned up clean.

It wasn’t until April 2017, when Kulbatski’s father’s blood tests showed an increase in his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, that the family became concerned. Kulbatski said they repeatedly asked his doctors to give him another CT scan, but they were told it was unnecessary because it was such a small increase.

Nearly a year later, Kulbatski’s father started having trouble eating and experienced constipation. His family doctor gave him an abdominal ultrasound and she discovered he had cancer growths in his liver. When the specialist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre agreed to give him another CT scan following the ultrasound, the results were just as Kulbatski feared.

“They [the growths] were in his lymph nodes, in his abdomen, in his pelvis, in the chest area, in the liver,” Kulbatski told CTVNews.ca during a telephone interview on Friday. “It was everywhere.”

Three months later, Kulbatski’s father was dead.

To make sense of what happened to her father, Kulbatski, a medical researcher and science writer, began writing blog posts about his treatment and the toll it took on her family. As she pored over the limited information she could glean from her father’s online patient portal, which she had access to, she says she discovered an addendum on his 2016 CT scan report.

Kulbatski said the message, which was added to the 2016 scan after it was compared to the CT scan in 2018, noted that there were in fact enlarged lymph nodes in her father’s stomach, abdomen, and pelvis at that time.

“In 2016, it had already started to spread,” she said. “Somebody failed to appropriately read and report on that CT scan and they missed it. He had at least two years, during which he could have received appropriate and timely care.”

Requesting records

Following the discovery of the addendum to the CT scan report from 2016, Kulbatski said she wanted access to all of her father’s medical records and not just the ones available on the online patient portal.

“I wanted his full medical file from the hospital so I can dig deeper, see if I can find the truth, and then bring it to their [the doctors’] attention,” she said.

On June 18, Kulbatski filed a formal request for his records with the University Health Network (UHN), which oversees the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and Toronto General Hospital, where her father also received treatment.

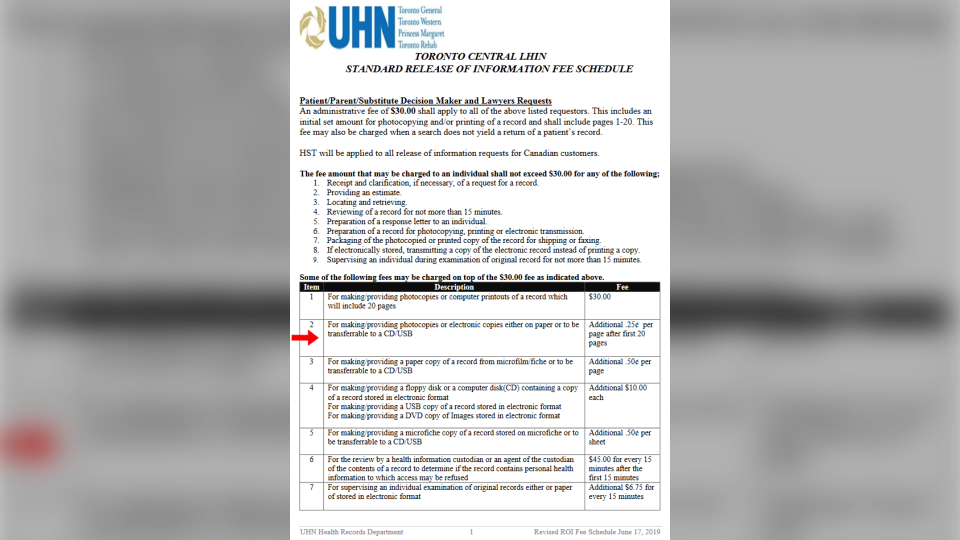

Kulbatski said she checked UHN’s fee policy, which was posted on its website with the date April 26, 2011, to see how much it would cost to have her father’s electronic medical records transferred to her on a CD. The policy, which she took a screengrab of, stated there would be a $30 administrative fee and an additional $10 for the CD, Kulbatski said.

Shortly after, Kulbatski said she was shocked to receive an invoice for more than $1,100. The invoice charged her the $30 administrative fee, the $10 for the CD, and 25 cents per page after the first 20 pages of her father’s 3,000-plus-page medical file.

When Kulbatski said she returned to UHN’s website to check its fee policy again, she discovered it had been changed to include a new section outlining the 25 cent per page charge for electronic records. That charge had only been for printed copies in the old policy, Kulbatski said.

To make matters worse, Kulbatski said the new policy was backdated to June 17, 2019 – one day before she submitted her request for her father’s records.

“Of course, now that’s what it says online because I brought it to their attention,” she said. “They didn’t even know what their own policy said.”

Alexandra Radkewycz, a senior public affairs adviser for UHN, said the online fee schedule was updated on June 17 to “provide more detailed information about costs over and above” the initial $30 administrative fee.

“These extra costs – which are not new - pertain to things such as converting often extensive paper records to electronic files, and careful review of files for accuracy,” she wrote in an emailed statement to CTVNews.ca on Friday. “All these extra costs are standard costs in Toronto hospitals.”

Radkewycz acknowledged that medical staff should notify the person requesting access to the records that the cost could be high if it’s a large file.

“We will reinforce this step with our internal staff,” she said. “Further, we will review information on the website for clarity going forward so that misunderstandings about costs do not reoccur.”

Kulbatski said she has submitted an appeal of the charges to Brian Beamish, Ontario’s information and privacy commissioner (IPC), and complained to her local MPP. She said after all of that, UHN offered to reduce the fees by 50 per cent.

On Friday, Radkewycz said UHN would reissue the invoice at $40 because “the timing of the request and the online fee update coincided.” She said the complete medical record is now available on a CD for Kulbatski to collect.

‘Barrier to transparency’

Despite the revised invoice, Kulbatski said her experience speaks to a larger problem of access to information in the health-care system.

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s an obstruction to access to medical information. That’s not an accessible fee and it goes against the recommendations of the information and privacy commissioner of Ontario,” she said.

In a 2010 dispute decision report, the IPC referenced its proposed fee regulations for the Personal Health Information Protection Act, in which it states that fees should not exceed $30 if “the record is stored in electronic form, electronically transmitting a copy of the electronic record instead of printing a copy of the record, and shipping or faxing the printed copy.”

The language used in the actual act is more vague and states that “the amount of the fee shall not exceed the prescribed amount or the amount of reasonable cost recovery.”

Kathleen Finlay, the founder of the Toronto-based advocacy group The Center for Patient Protection, said Kulbatski’s experience is nothing new.

“It happens all the time,” she said during a telephone interview on Saturday. “It’s one of the most frequently raised issues when people come to The Center for Patient Protection and I’ve been doing this for the last seven or eight years.”

Finlay said when hospitals charge exorbitant fees for these types of requests, they’re placing an extra burden on people who are most likely already experiencing financial hardship from missing work, transportation and accommodation costs.

“This all puts a lot of financial burden on families so when they get hit with an outrageous bill, most of them can’t deal with it,” she explained. “And that’s a barrier to transparency that’s just not acceptable in our system.”

Instead of discouraging people from becoming involved in their own or loved ones’ care, Finlay said Canada’s health-care system should be encouraging them to take an active role.

“You want them to have confidence that the care was of the quality and appropriateness that it needed to be,” she said. “You want to make it easy for them to view the records and you want to make it easy for them to follow up and ask questions. If you don’t have anything to hide, you shouldn’t worry about that.”

For Kulbatski, she said she wants UHN to implement some new policies and practices so that other patients and their families don’t have to go through what she did.

“UHN should not be putting people through this sort of hardship in order to get the medical file,” she said. “It should be easier to access the truth.”