LONDON -- The new respiratory virus that emerged in the Middle East last year appears to make people sicker faster than SARS, but doesn't seem to spread as easily, according to the latest detailed look at about four dozen cases in Saudi Arabia.

Since last September, the World Health Organization has confirmed 90 cases of MERS, the Middle East respiratory syndrome, including 45 deaths. Most cases have been in Saudi Arabia, but the mysterious virus has also been identified in countries including Jordan, Qatar, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Tunisia. MERS is related to SARS and the two diseases have similar symptoms including a fever, cough and muscle pain.

"At the moment, the virus is still confined (to the Middle East)," said Dr. Christian Drosten of the University of Bonn Medical Centre in Germany, who wrote an accompanying commentary. "But this is a coronavirus and we know coronaviruses are able to cause pandemics."

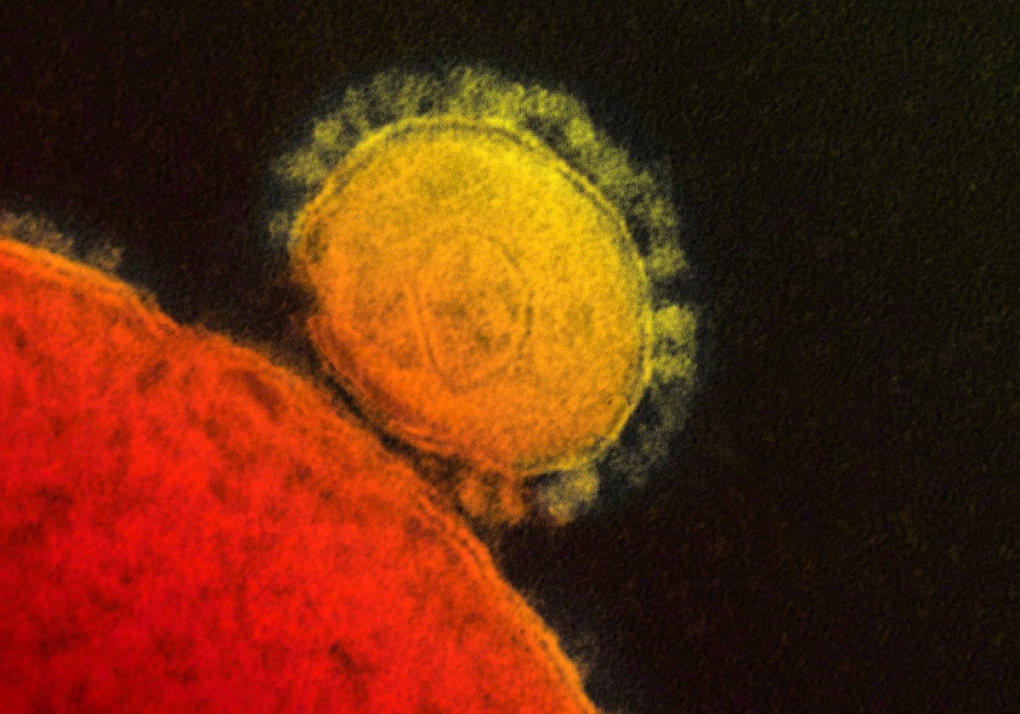

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that mostly cause respiratory infections like the common cold, but it also includes SARS, the virus that killed about 800 people in a 2003 global outbreak. MERS is distantly related to SARS but there are major differences between the two. Unlike SARS, MERS can cause rapid kidney failure and doesn't seem as infectious.

Drosten said the upcoming hajj in October -- where millions of Muslim pilgrims will visit Saudi Arabia, where the virus is still spreading -- is worrisome. On Thursday, WHO said in a statement that the risk of an individual traveller to Mecca catching MERS was considered "very low." The agency does not recommend any travel or trade restrictions or entry screening for the hajj.

In the latest study, researchers found 42 of the 47 cases in Saudi Arabia needed intensive care. Of those, 34 patients deteriorated so badly within a week they needed a breathing machine. That was up to five days earlier than was the case with SARS. Most of the MERS cases were in older men with underlying health problems, as one of the biggest outbreaks was among dialysis patients at several hospitals. The research was published Friday in the journal, Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Ali Zumla, one of the paper's co-authors and a professor of infectious diseases at University College London, said in an email that the rapid deterioration of patients was "not worrying at all since the numbers are small" and most of the patients had other health problems.

Drosten, however, said that could be bad news. "That could mean the virus is more virulent and that (doctors) have a smaller window of opportunity to intervene and treat patients," he said. Detecting MERS fast could be a problem since quick diagnostic tests aren't available.

Last week, WHO declared there was not yet enough evidence to classify MERS as a public health emergency after setting up an emergency committee to keep a closer eye on the virus.

Zumla said it was "very unlikely" that MERS would ignite a pandemic. He noted officials were increasingly picking up mild cases of the disease, suggesting reported cases were only the tip of the iceberg. Identifying more mild or asymptomatic cases could indicate the virus is more widespread, but it's unclear if those infected people might be able to spread the disease further.

MERS also appears to be mainly affecting men; nearly 80 per cent of the cases in the new study were men. Drosten said there might be a cultural explanation for that.

"Women in the (Middle East) region tend to have their mouths covered with at least two layers of cloth," he said, referring to the veils worn by women in Saudi Arabia. "If the coronavirus is being spread by droplets, (the veils) should give women some protection."

Scientists still haven't pinpointed the source of MERS and theories have ranged from animals like goats and camels to dates infected with bat excrement. WHO says the virus is capable of spreading between people but how exactly how that happens -- via coughing, sneezing or indirect physical contact -- isn't known.