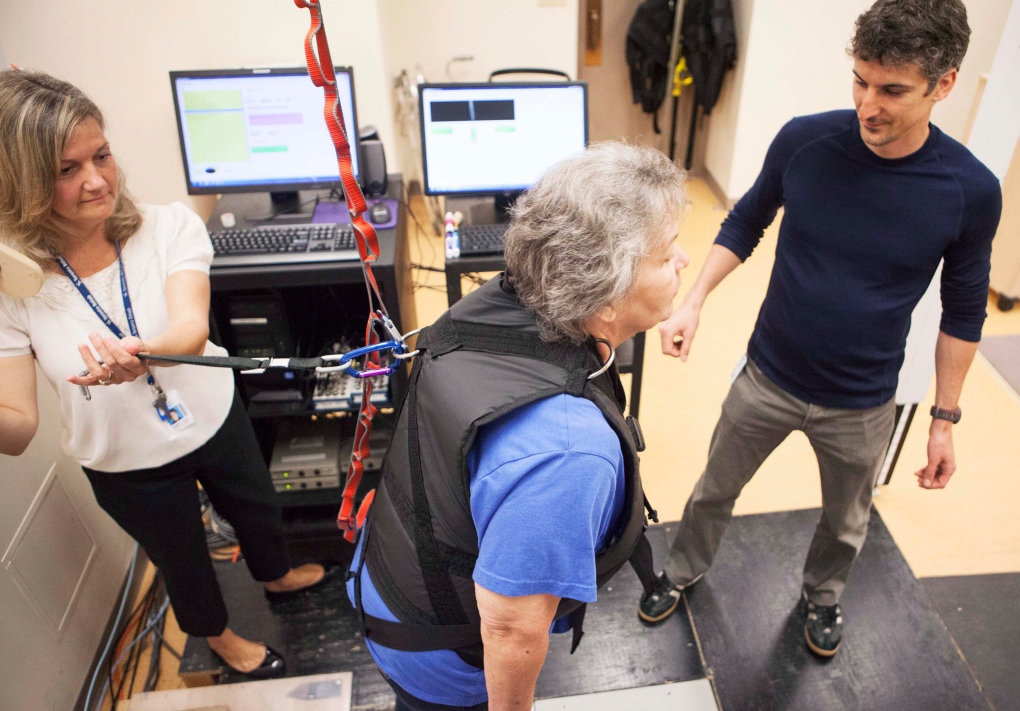

TORONTO -- Janet Raymond leans forward, her upper body supported by a vest-like harness suspended from the ceiling. She's waiting for the apparatus to deliver the jolt she knows is coming, its goal is to test how steady she is on her feet.

There's an abrupt release of tension on the harness and Raymond lurches forward, her face betraying a touch of uneasiness, despite having gone through this manoeuvre many times before.

But she's kept her footing and hasn't fallen -- and that means she's making progress.

About eight months ago, Raymond was about to board a Toronto streetcar after a night out with friends, when her legs suddenly felt too weak to mount the vehicle's stairs.

It turned out she had suffered a mild stroke, which affected her right leg and part of her hand. After a stay in hospital, Raymond was transferred to the stroke unit at Toronto Rehab, where therapists took over her recovery.

"When I first arrived, I couldn't walk at all," says Raymond, 62. "I was in a wheelchair. I was quite upset and I wondered what was going to happen, if I'd be in a wheelchair all my life."

Her goal was to walk again, to go back to work as a delivery driver and to return to everyday activities with her husband.

That's when staff at the Balance, Falls and Mobility clinic at Toronto Rehab kicked into high gear.

The recently created program is designed to assess patients' balance and walking ability using state-of-the-art computerized technology.

"We have developed a clinic where individuals come from the stroke unit or from our brain injury in-patient unit and they get a very sophisticated assessment based on some of the research that we're doing," says Dr. Mark Bayley, medical director of the brain and spinal rehab program.

"And we provide them with a treatment plan based on that assessment."

One of those assessment tools, and indeed recovery tools, involves having patients "fall" or go off balance while wearing a protective harness.

Strapped into the gear, the patient stands on pressure-sensitive force plates that transmit data to a computer, which maps how their footing changes in response to the controlled fall -- a "perturbation" in rehab-speak.

"We look at their reactions to that perturbation and try to improve that through training them," says Bayley.

Another piece of the assessment-training equipment is a pressure-sensitive gait mat, which records a patient's steps as they walk, transferring their footfalls in real time to a computer screen.

"The person walks on the mat and it's able to pick up footfalls and give us a whole bunch of information, quantitative information, about how that person is walking -- how quickly, what their stride length is, how variable they are in their walking," explains clinic leader Liz Inness.

"And again, we might be able to compare how they walk with their cane, without their cane, with or without an orthotic, under different conditions, so we can tailor our therapies."

Inness says using these more technological assessments goes beyond what therapists can glean about a patient's mobility strictly through observation.

Seeing how a patient's feet land can reveal underlying issues that might be affecting balance control or gait, so that therapy can be more specifically targeted.

"Balance and mobility issues are a huge problem after someone has a stroke or a brain injury," she says. "It can affect their risk for falls when they return to the community. It can also affect their day-to-day life.

"When we're out in the community, we are experiencing countless perturbations to our balance just to be able to walk, negotiating crowds, walking on the sidewalk.

"And this allows us to assess underlying issues we need to address in therapies to help people become more mobile and return to the community in a safe and independent way."

Toronto Rehab is also developing portable tools using such game-based devices as Nintendo Wii balance boards, which could be used in clinical settings outside the hospital.

"We're working to see if we can use those to provide the same measurements as in the clinic," says mobility team leader William McIlroy.

"Our bigger plan, our bigger initiative, is to transform not just the Toronto Rehab and not just in southern Ontario, but around the world about how people diagnose and treat balance and mobility challenges."

For Raymond, the program has meant a return to independence.

"You don't feel the same after you have a stroke," she says. "I had to learn how to walk all over again ... Eventually, I couldn't believe it, but I could walk. Every day was better.

"It gave me hope that I'm not going to be stuck in a wheelchair. I'm going to be walking and normal."