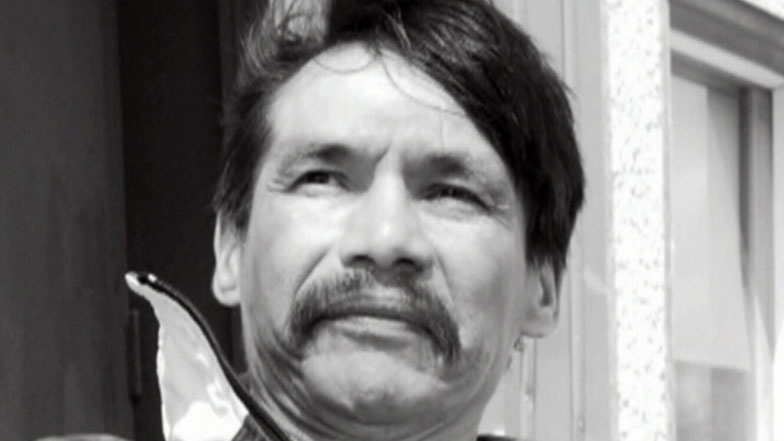

WINNIPEG -- Robert Sinclair feels the weight of his family's history when he has no choice but to go to an emergency room in Winnipeg.

He feels anxious, uncertain and sometimes angry.

A few years ago, he had a serious accident with a chainsaw in the woods and was taken to Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre. He figures his name must be known at the hospital because the care came immediately.

"I hit that little button, it's like they were standing at the door or something," he said. "They probably didn't want another Sinclair dying in their hospital."

It was a Friday afternoon 10 years ago when Robert's cousin, Brian Sinclair visited the same emergency room.

The 45-year-old had been in a wheelchair since he lost his legs to frostbite in 2007. After a visit to his community clinic that Friday, he was given a letter from his doctor and told to go to the Health Science Centre's emergency room to have his blocked catheter changed.

He checked in at the triage desk and wheeled himself over to a spot near security in the waiting room.

Over the next 34 hours, Brian Sinclair sat in his wheelchair, occasionally vomiting on himself and eventually succumbing to sepsis.

Later, it emerged staff assumed the man was homeless, intoxicated or had already been seen and was waiting for a ride. By the time his body was discovered, rigor mortis had already set in.

"It's terrible to remember that he actually died that way," Robert Sinclair said. "I'd like to think that he passed away teaching us all something, teaching us that as human beings we have become so insensitive to each other."

An inquest into Brian Sinclair's death, which began in 2013, concluded it was preventable and made 63 recommendations, largely about structures, procedures and hospital policy.

His family, and others, say it didn't address the real issue -- racism in the health-care system.

Robert Sinclair said Indigenous people regularly contact him to ask for advice or share their stories about facing racism in hospitals.

"The racism, the stereotyping, none of that has been addressed," he said.

Mary Jane Logan McCallum, a member of the Brian Sinclair Working Group and a history professor at the University of Winnipeg, said Indigenous people still face prejudice in the health-care system 10 years later.

"There are a number of people who have similar stories -- what people have been calling 'Brian Sinclair stories' -- where they have individuals in their family or their community who also experienced inadequate care," said McCallum, a member of the Munsee Delaware Nation in Ontario.

In her new book, co-written with University of Manitoba history professor Adele Perry, called 'Structures of Indifference: An Indigenous Life and Death in a Canadian City,' McCallum said Brian Sinclair's story shows how deep-seated racism in the community seeps into hospitals.

"If you talk to Indigenous people and you say, 'are you concerned about going to the hospital?' chances are they are still going to say, 'yes,"' she said. "There may have been some changes going on, but this is in no way an issue that has gone away and I don't think we can expect it to go away any time soon."

The health authority made changes to the layout of their emergency room, their triage procedure and other policies after Brian Sinclair's death. Lori Lamont, the authority's chief operating officer, said cultural training is now mandatory for staff and there is an increased focus on Indigenous health services.

"We failed him when he came to us for care. I think that we have learned a lot as a system as a consequence of that," she said. "We can't let our guard down. We need to continue to work on that."

Brian Sinclair's eldest sister, Joyce Grant, said she hopes her brother will be remembered as a kind and helpful person. Before he lost his legs, Grant said her brother saved two elderly people in a fire.

She still feels his presence but Grant said she doesn't think her brother will be able to rest in peace until there is justice for his avoidable death. The family filed a lawsuit against the health authority, but a resolution is likely years away.

"This shouldn't have happened to him. It's very, very sad, and I'm angry. I have a lot of anger about what happened," she said in an interview from Richmond, B.C.

Robert Sinclair plans to grab a coffee with Brian Sinclair's brothers on Friday, the anniversary of his death. They won't visit the place where he took his last breath, the downtown emergency room.

"It probably wouldn't bother me if I never went there again," he said.

"We just want Brian to be remembered as somebody who -- even though the way he passed away -- he's going to leave something behind and that's hopefully a better health-care system where they are going to be more attentive to people regardless of race."