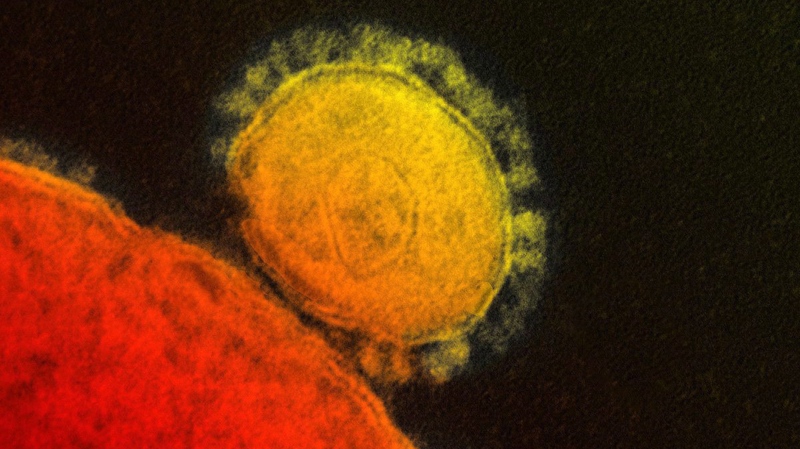

TORONTO -- New research is adding weight to the idea that a combination of existing drugs may help some patients infected with the new MERS coronavirus.

The findings could prove to be important because there is no vaccine to prevent the infection and no drugs specifically designed to mitigate the damage it does in severe cases.

Infections with the new virus continue to pile up, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

On Saturday the World Health Organization put the global count of MERS infections at 114 with 54 deaths. But since then Saudi authorities have announced eight additional cases, three of them fatal. That will push the global total to 122 cases and 57 deaths.

The new research into the drug combo shows it helps reduce the severity of disease in macaque monkeys deliberately infected with MERS. While the regimen was previously tested in kidney cells from monkeys, these findings are the first showing what happens when the drugs are used in living animals.

Macaques given ribavirin and interferon alpha 2b after having been infected with the MERS coronavirus were less sick than infected animals that weren't given the therapy. As well, follow-up autopsies of the treated and untreated animals showed lower levels of virus in tissues and less lung damage in the treated animals.

"Everything fit together towards suggesting that treatment definitely helps lead to a better outcome than the absence of treatment," said Darryl Falzarano, a Canadian scientist who is the lead author of the study, published Sunday in the journal Nature Medicine.

The work was done at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont. Falzarano is currently a visiting fellow at the facility.

When the new coronavirus first hit the scientific community's radar about a year ago, several labs began trying to figure out if drugs already in the world's medicine cabinet might help combat the disease the virus triggers.

Developing a new drug from scratch can take years. Persuading a pharmaceutical company the sales potential warrants production, pushing the new compound through clinical trials and securing regulatory approval adds tens of millions of dollars in costs and additional years to the process.

If MERS starts to spread more widely among people, the world wouldn't have that kind of time, scientists reasoned. So they started to test old drugs, alone and in combination.

Interferon alpha 2b is a synthetic version of a protein made by the human immune system. Ribavirin is an antiviral drug used for infections like hepatitis C. It was also widely used during the 2003 SARS outbreak; MERS is from the same family of viruses as SARS.

While ribavirin was a natural place to start for MERS, it's not clear the drug was actually useful in treating SARS. The explosive start and short duration of the outbreak meant there was no time to conduct clinical trials looking at whether the patients who got the drug were more likely to survive.

While the macaque testing looks promising, there are some important caveats. As a result, teams like the one at the Rocky Mountain Labs are continuing to test other options looking for better tools with which to treat MERS.

One of those caveats relates to a shortcoming of the macaque model, so far the only known animal model for laboratory work with the MERS virus.

Macaques can be infected with the coronavirus, but the ensuing disease do not fully reflect what goes on in when humans contract the virus. The monkeys develop mild to moderate infections when exposed to MERS, but they do not get as profoundly ill as many human cases do.

"At the moment, this is as good as it gets," Dr. Heinz Feldmann, chief of virology at the Rocky Mountain Labs and senior author of the paper, said of the animal model.

Of the findings, he said: ""Our job is to provide options, and this is certainly one. Whether they consider this a good one or not, it's up to the physicians."

As both drugs have long been in use, there are no regulatory hurdles doctors would need to clear to try the combination in MERS patients. Still, that doesn't mean they will rush to use the regimen.

"There are doctors who don't have much problem using ribavirin and interferon (alpha 2b), and there are physicians that have all kinds of problems to use ribavirin and interferon," said Feldmann, suggesting side-effects of the drugs may scare off some practitioners.

The therapy has been tried in some cases in Saudi Arabia, the country's deputy minister of health said via email.

"We have used this combination regimen on a group of patients but it's not routinely used in all patients," Dr. Ziad Memish said.

The cases in which the drug combo was used were severely ill, he said, with therapy starting late in the course of the disease. Because of that, Memish said, "the outcome has not been very positive."

Another scientist working to identify drugs and develop a vaccine to use against MERS praised the work outlined in the study, but said more research is needed to see whether this drug combination should be used, especially in severely ill patients.

"I think as an initial study, it's well done and it gives us a lot of information to start identifying what other experiments should be followed up with in future," said Matt Frieman, a coronavirus researcher and professor of virology at the University of Maryland medical school in Baltimore.

"The leap between that data and treating a person infected with MERS who has other co-morbidities -- I think it needs to be studied further," Frieman said.

Many of the most severe MERS infections have occurred in people with "co-morbidities" -- pre-existing diseases like diabetes and cancer which would influence the outcome of the infection.

Frieman suggested it would be helpful to suppress the immune systems of macaques -- in essence mimicking what diabetes or cancer might do to the immune system -- and then rerun the study to see if the drug combo was effective under those conditions.