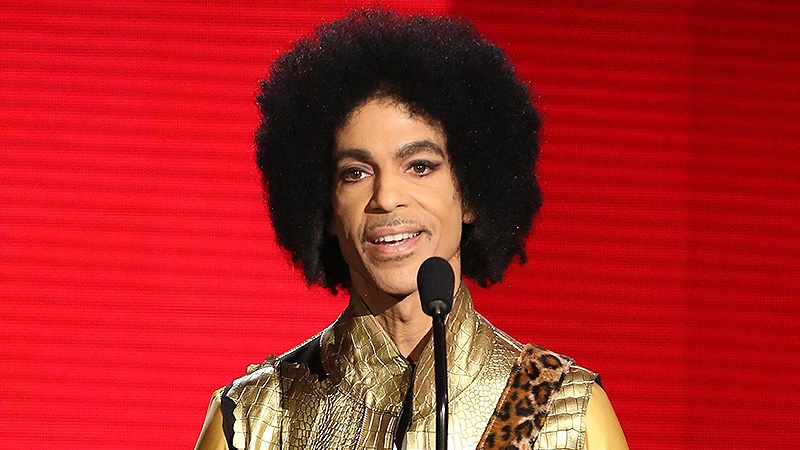

CHICAGO -- Prince's final days and unexpected death at age 57 raise questions among experts familiar with prescription painkiller overdoses. It's possible the innovative musician's demise represents one of the most public tragedies in an overdose crisis now gripping America.

A law enforcement official told The Associated Press last week that investigators are looking into whether Prince died from an overdose and whether a doctor was prescribing him drugs in the weeks before he was found dead at his home in suburban Minneapolis. The law enforcement official has been briefed on the investigation and spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

And on Wednesday, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that representatives of Prince had reached out to a California doctor to help the musician kick an addiction to painkillers.

An attorney for Dr. Howard Kornfeld told the newspaper that Kornfeld's son, Andrew, arrived at Paisley Park the morning of April 21 to discuss treatment. Andrew Kornfeld -- who works in his father's practice -- called 911 when Prince's body was found in an elevator.

Whether Prince was addicted to painkillers is uncertain, but some are wondering whether the stigma surrounding addiction may have prevented Prince -- who built a reputation as a sober superstar -- from seeking help in time if he was becoming dependent.

------

DOES PAIN TREATMENT LEAD TO ADDICTION?

With good management and no history of addiction, opioids can help people find relief from pain with only a small risk of causing addiction, according to a 2010 systematic review of the available studies.

"If you do not have a past history of addiction and are in your 40s and getting pain treatment with opioids, your odds of becoming newly addicted are low," said Maia Szalavitz, author of "Unbroken Brain," a newly published book about addiction. "One study of thousands of ER visits for overdose found that only 13 per cent of victims had a chronic pain diagnosis."

If Prince had become addicted, Szalavitz said, he may have shunned seeking help.

"The stigma that is associated with addiction could well have been what killed him," she said. "Maybe he was afraid to seek help. Maybe he sought help before and was treated in a disrespectful and unproductive way."

------

WHAT IS NALOXONE?

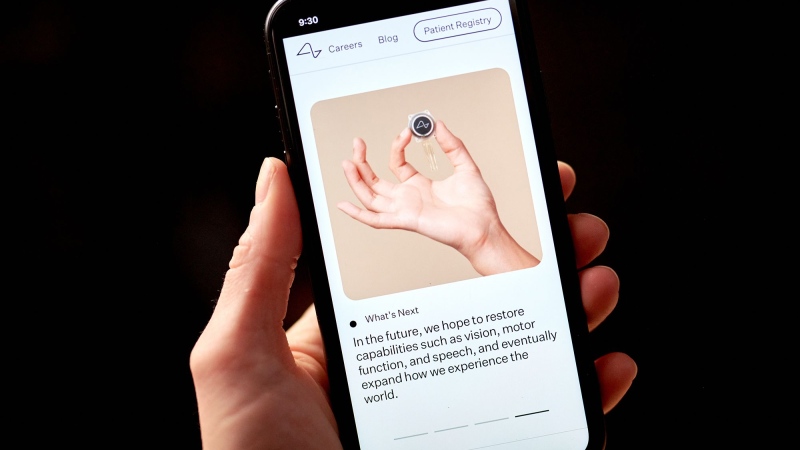

The overdose antidote naloxone has been saving lives for decades, reversing the effect of opiates since it was first approved in 1971. Hospital emergency rooms and ambulance crews use an injectable generic version to revive people whose breathing has slowed or stopped during a drug overdose.

Needle-exchange programs in many cities distribute take-home naloxone kits to active drug users. Many experts consider these giveaways of generic injectable naloxone to be a public health success story that has saved thousands of lives.

Newer to the market are brand-name versions of naloxone -- a nasal spray and a "talking" auto-injector that gives instructions. The syringe-free products have prompted new efforts to get naloxone kits to fire departments, police, parents, pharmacists and school nurses.

One of the naloxone products, Narcan, was used after Prince's plane made an emergency stop in Moline, Illinois, on April 15 and he was found unconscious on the plane, the law enforcement official told the AP. The official said the so-called "save shot" was given when the plane was on the tarmac in Moline as Prince returned to Minneapolis following a performance in Atlanta.

Narcan is carried by Carver County sheriff's department officers, Sheriff Jim Olson said at a news conference April 22. But he added that the overdose antidote drug was not used by first responders as they tried to revive Prince at his home on April 21.

------

HOW DOES NALOXONE WORK?

Naloxone works by reversing the effects of opiates in the brain and at higher doses can immediately trigger withdrawal symptoms like nausea. Some drug users wake up cursing emergency personnel for ruining their high. Dr. Steven Aks, emergency medicine physician and medical toxicologist at Stroger Hospital in Chicago, has seen it happen.

Aks has revived many patients with a naloxone shot. "Too many to count," he said. It's an almost daily occurrence in the Chicago ER.

"They will come into the emergency department not breathing, with small pupils. They're out of it. You can't wake them up. If you give an injection of naloxone, they start breathing better. They will sit up," Aks said. "If you give them too much they can go into withdrawal and feel sick. They'll feel nauseated, start having stomach cramps and pain throughout their muscles."

After naloxone, it's a good idea to keep a patient under observation for about four hours, Aks said. When naloxone wears off, a patient can stop breathing again from opiates still flooding their system.

"If you need multiple doses of naloxone (to revive a patient) they should stay overnight," he said.

Aks also said more hospitals are educating overdose patients about naloxone and sending them home with kits, so friends and family can be ready with the life-saving antidote.