TORONTO -- At age 70, retired nurse Donna Lessard can expect to be towards the front of the line for a COVID-19 vaccine when supply and distribution expands in coming months.

But instead, she's opted for an unproven vaccine candidate she can have now -- a two-dose product by the Quebec City-based biopharmaceutical Medicago currently running Phase 2 clinical trials.

Because the trials are blinded, the Montrealer doesn't know if last month she received a second dose of the prospective vaccine or a placebo, and may not know for a year -- well after most Canadians are expected to receive one of several licensed vaccines.

Lessard admits her decision could put her at risk of COVID-19 infection much longer than other seniors, but says there are many people who need approved vaccines more urgently than she does.

"I'm not in a nursing home, I'm in excellent health," says Lessard, who was a nurse for 50 years before retiring in 2020. "There are a lot of other people, rightly so, that would go before me."

Despite the willingness of senior trial participants like Lessard, whether and how to include seniors in COVID-19 vaccine trials poses thorny ethical questions now that effective vaccines are available and more are soon to come, says University of Toronto bioethicist Kerry Bowman.

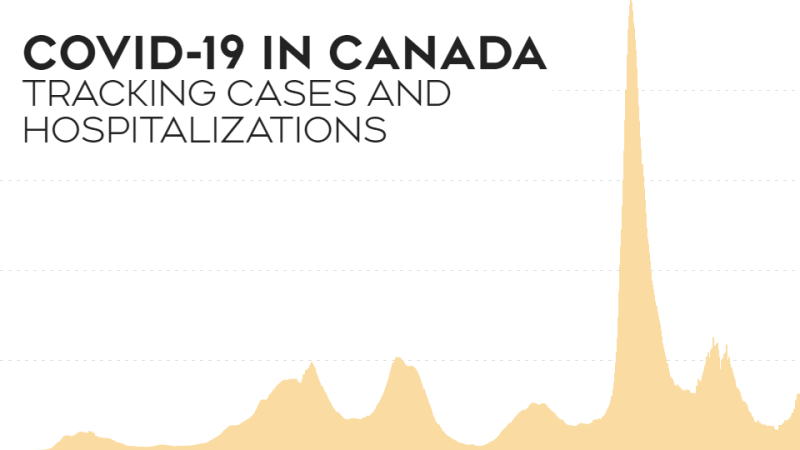

Seniors, by far, have been hardest hit by the novel coronavirus, with about 70 per cent of Canada's COVID-19 deaths involving people aged 80 and older, and nearly 20 per cent between the ages of 70 and 80.

The emergence of more infectious variants adds even more uncertainty to the pandemic, especially after one version was linked to a devastating outbreak that engulfed a Barrie, Ont., long-term care facility and killed dozens of residents.

"I generally don't think it's justifiable right now having senior citizens in completely blinded trials," says Bowman.

"We can't fully quantify risks, which I think is significant…. The variants are the wild card now. We don't even know which way this is going and the whole situation could get a lot worse very quickly."

Still, there can be exceptions for healthy volunteers such as Lessard, especially if the trial is designed to minimize potential harms, Bowman allows.

The Medicago trial limits its use of placebos as one way to do that -- the company says that for every volunteer who gets a saline injection, five participants receive the proposed vaccine.

That's instead of splitting volunteers equally between the placebo and treatment groups, more typical in double-blinded trials trying to assess how effective a proposed drug really is.

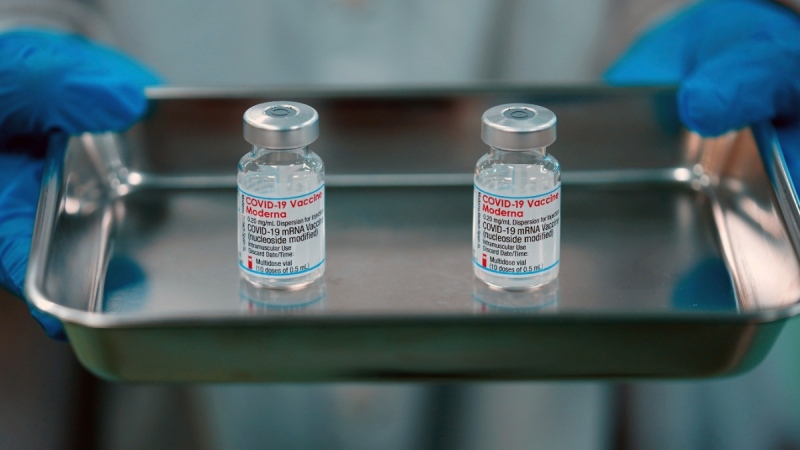

Given the risks posed by the ongoing pandemic, infectious disease physician Zain Chagla suggests it would more appropriate to compare vaccine hopefuls to already proven options, which in Canada are by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna.

It's hard for researchers to say they're not causing harm if they effectively deny someone a proven drug, says Chagla, an associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton.

"Many of these trials will have to eventually have some implementation of a standard-of-care drug, which might be Pfizer," Chagla says of placebo arms.

"And then at the end, make sure that everyone who got the (tested) drug also gets Pfizer," says Chagla, adding the caveat that there are still uncertainties about what happens when someone takes two different COVID-19 vaccines.

All clinical trials undergo multiple ethics and protocol reviews by the drug developer and Health Canada to ensure patient safety remains paramount, says Karri Venn, president of research at LMC Manna Research, which is running multiple trials for various biotechs, including Medicago's vaccine trial.

And trials don't typically start with seniors or other vulnerable groups. Only if Phase 1 establishes safety among healthy adults would studies expand to older volunteers, with later trials adding in adolescents, children and pregnant women.

Venn says COVID-19 has added novel complications to scientific research, and suspects it could soon become difficult to recruit and keep seniors committed to clinical trials if they know an approved vaccine is imminent.

"This is for the first time posing a lot of challenges for the traditional way in how you would do research, to be honest with you," says Venn, expecting some volunteers sign up planning to quit as soon as they're eligible for other, approved options.

"They may say, `I'm going to take (this proposed vaccine) and in nine months I'm going to say, "You know what? Unblind me."' … There's all of that happening, too. It's a very unusual time."

It's very rare to unblind a participant partway through a trial, Venn adds, and if it does happen, it's almost always for a medical or safety reason.

But all trials must release any participant who wants to quit, no matter the reason, she says, and their data wouldn't be included in the final results.

Giving seniors a placebo is out of the question for Providence Therapeutics CEO Brad Sorenson, who is planning Phase 2 trials for his COVID-19 vaccine hopeful.

The head of the Calgary-based biotech says his recently launched Phase 1 safety trials include a placebo group, but no seniors. Phase 2 will likely include seniors but no placebos.

"We don't want to include a placebo group for people that are older and at a higher risk. Not when there's a vaccine that would be available to them," says Sorenson, musing on a possible workaround.

"We can do a comparative study where they get either our vaccine or a Moderna vaccine."

Assuming the trial can get its hands on these approved vaccines -- allotments from Moderna and Pfizer are both facing significant distribution delays in Canada.

Bowman sympathizes with volunteers who consider unknown protections of a trial vaccine to be better than nothing. He suggests those who consent to the terms of clinical trials do so "under duress."

"Before Christmas, we were told we'd be swimming in vaccines by now, and we're really, really not," says Bowman.

"People have to protect their own lives and well-being."

Still, concrete data on how seniors respond to prospective COVID-19 vaccines is crucial, especially with relatively few therapies and so much still uncertain about the disease, says Medicago's senior director of scientific and medical affairs.

"I know it's a big request, but it's part of science and that's how it works and that's how we make sure the product is good, that the people receiving it are safe," says Nathalie Charland.

"There are constraints related to the trial, we are aware of that, and that's why we say a big thank you to all those who are involved in our trials."

Charland says Medicago's Phase 2 trial has already collected the data it needs from hundreds of senior volunteers in Canada and the United States, but recruiting the thousands more needed in Phase 3 will be tougher.

Half of the 30,000 participants needed are seniors, and half of all volunteers would get a placebo, she says.

"We are already planning for dropouts. We are very conscious that this might -- and probably will -- happen but Phase 3 is an efficacy trial so we have to go in regions of the world where the virus is circulating a lot," she says, noting prospective sites include Latin America and Europe.

"It will be in countries where there's not that many vaccines distributed yet. So that should help recruit subjects."

Lessard suspects she got Medicago's vaccine candidate, citing a slight headache and sore arm after the first dose and another sore arm after the second dose.

But she says that was not her primary reason for joining the trial, expressing hope her involvement will serve a greater public good.

"There's a lot of fear around the COVID vaccines and we still hear people saying, 'Oh, I'm not going to take the vaccine until it's perfect,"' says Lessard.

"And my attitude is: Well, how are we going to get it perfect if nobody volunteers? And if not now, when? It's got to be done now."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 7, 2021.