CALGARY -- A filmmaker says Neil Young's trip to Alberta's oilsands seemed more about showcasing the Canadian singer's eco-friendly car for a documentary than about learning about the industry.

Tim Moen has lived in Fort McMurray for 13 years and was contacted by Young's production company, Shakey Pictures, to shoot aerial footage.

Moen said he spent a couple of hours in a helicopter last week mainly shooting Young's hybrid 1959 Lincoln Continental driving on the highway near Syncrude and Suncor with the oilsands as a backdrop.

"As a film producer, I understood that his goal was to contrast green technology against dirty oil, so to speak, so I wasn't expecting him to do any kind of balanced expose on the community," Moen said in an interview with The Canadian Press. Young was here primarily to contrast green energy with what he sees as dirty energy, Moen added.

"When you look at what your client is shooting and not shooting, you get a pretty good sense of what their agenda is. They wanted shots of tailings ponds, industrial plants and they wanted shots particularly of their green vehicle driving in front of these dramatic landscapes, and that was their primary goal."

Young spent a few days in the Fort McMurray area. He drove the Continental, which runs on ethanol and electricity, up to the oilsands region while traversing the continent from his California home to Washington.

He came away comparing what he saw to the scene of an atomic bomb strike.

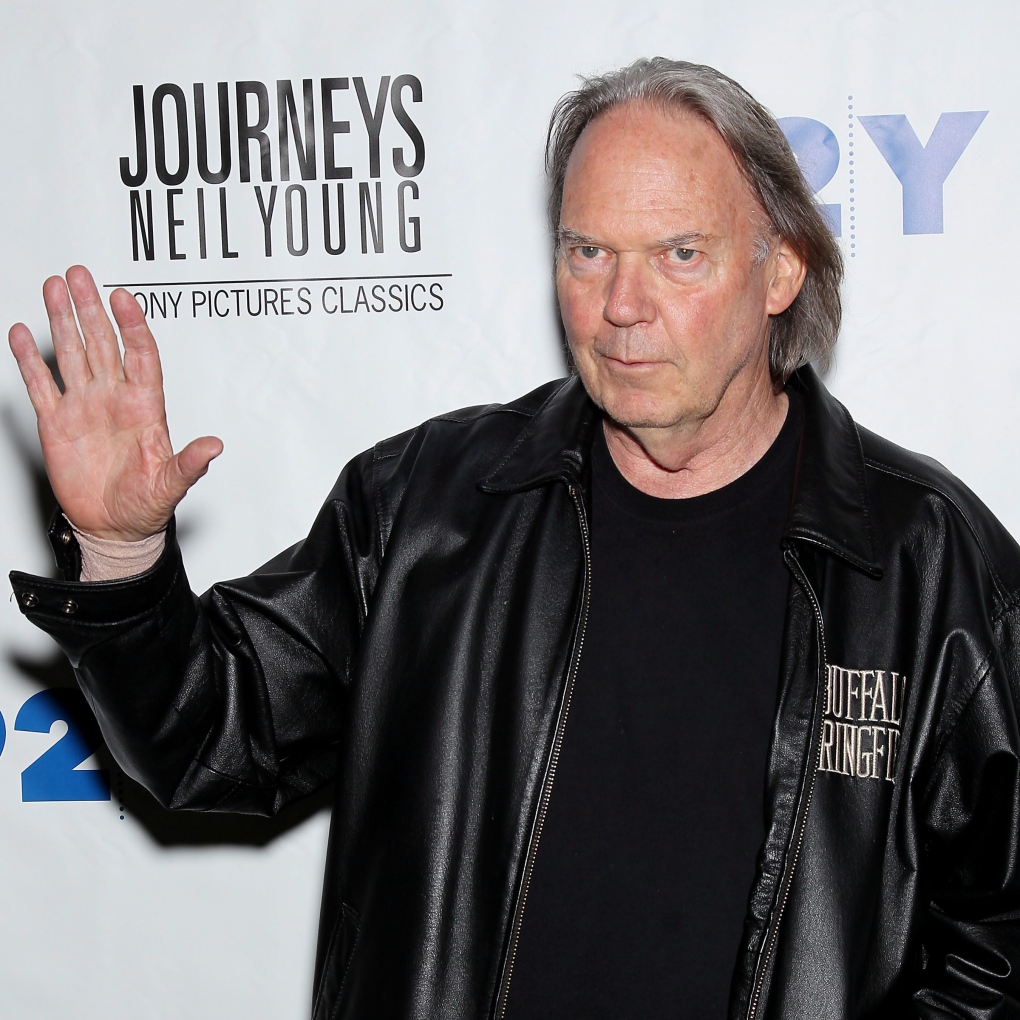

"The fact is, Fort McMurray looks like Hiroshima,"' Young, 67, said at an event Tuesday in Washington held by Democratic Sen. Harry Reid and the National Farmers Union.

"Fort McMurray is a wasteland. The Indians up there and the native peoples are dying. The fuel's all over, there's fumes everywhere. You can smell it when you get to town."

Young declared himself against the Keystone pipeline, which would carry oilsands product through the United States to the Gulf Coast. The singer's comments sparked a backlash in Fort McMurray. A local rock radio station stopped playing the Canadian singer's music.

Moen said he's still a "big fan," but was disappointed with Young's remarks. He wrote a blog about his experience.

"The only thing I knew for sure was that the documentary was about Neil's 1959 Lincoln Continental convertible that he had a team of specialists convert into a cellulosic ethanol burning hybrid dubbed The Lincvolt," Moen wrote.

"What we didn't shoot was as informative about the narrative as what we did shoot. We did not film any reclaimed land. We didn't film any new extraction operations using greener technology. We didn't film any industry experts.

"We didn't film Neil's diesel burning bus that his crew rode in. We didn't film the environmentally conscious community active in Fort McMurray. That stuff wasn't on the agenda."

Young, who was accompanied by actress Daryl Hannah, also spent time with the chief of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, a community downstream from the oilsands that believes the industry's rapid growth is making people sick.

"They reached out to the ACFN, so I bridged those connections," said Eriel Deranger, communications co-ordinator with the band. "They were just really interested in what was happening in the region."

Deranger said she rode up to Fort McMurray from Edmonton with Young and Hannah and the topics of conversation included the story behind Young's car and issues in the Fort McMurray area.

"They had questions about the industry and the kind of things that have been going on in the region."

Deranger said the band has been pushing government to create better consultation policies and ways to let First Nations be part of the development of projects from beginning to end.

"It was more discussions around the fact that it's out of control and we need to move in a way to make it more sustainable and more responsible," she said.

"We're not talking about shutting down the tarsands. We're talking about slowing down the pace of scale and looking at viable ways for reclamation and remediation in the region and adequate compensation."