TORONTO -- Advocates are calling for the reclamation of Hogan’s Alley, a historic Black community in Vancouver that was demolished more than 50 years ago when the city decided to build a viaduct over the area.

It’s where many of British Columbia’s first Black immigrants settled after migrating to the province in the early 1900s, and became a flourishing neighbourhood with a vibrant arts and food culture.

The Hogan’s Alley Society has been at the forefront of the fight in returning the community back to the hands of Black Vancouverites. The society has created a petition to demand for the city’s reconciliation of demolishing Hogan’s Alley.

“The intentional displacement of Vancouver’s only Black neighbourhood in the decades spanning from the 1940s to the 1970s, marks an important and often erased history of people of African Descent who struggled to exist and thrive in the spaces to which we have been relegated,” the petition reads.

Amid worldwide anti-Black racism protests following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police -- protests that continued Friday during the U.S. celebrations of Juneteenth -- the petition has gained added urgency.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

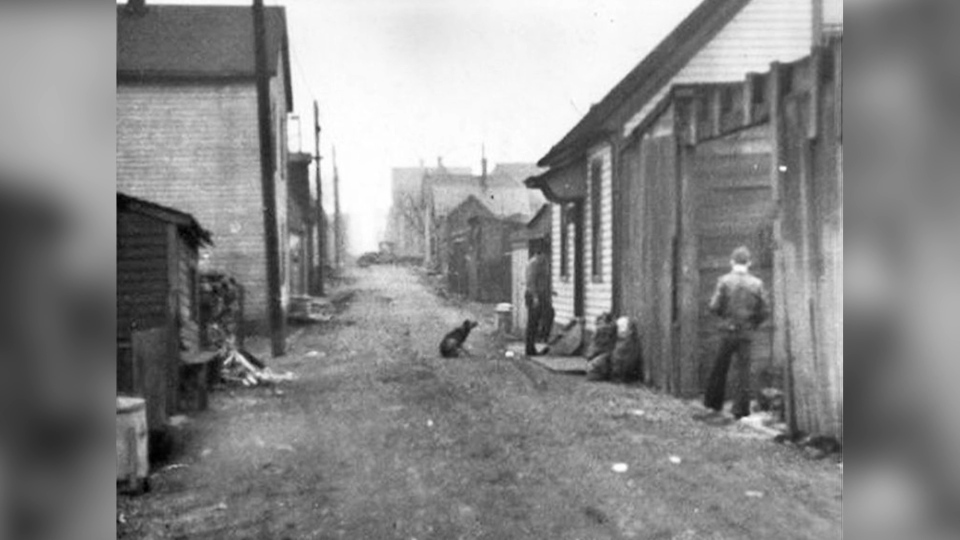

Hogan’s Alley is the unofficial name for Park Lane, a four-block alley that ran through the neighbourhood of Strathcona in Vancouver during the 1900s all through the 1960s.

“This is where you would go to find Black folks. This is where we would be allowed to live,” said Stephanie Allen, the founder of the Hogan’s Alley Society.

The community was built out of Black Vancouverites seeking asylum from racial violence and thrived to become a staple for the Black community.

“We had Black women entrepreneurs here and a lot of Black men brought up from America to work on the railroads,” Allen said to CTV News.

Hogan’s Alley was also home to the city's only Black church, the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel, what Allen calls the heart of the community. Iconic businesses were created within the small area such as the Pullman Porters’ Club and Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, where Nora Hendrix -- grandmother of Jimi Hendrix -- worked. Speakeasies were also popular, some of which were visited by visiting Black musicians like Sammy Davis Jr.

Though the community was active for decades, it wasn’t immune to continued racism and threats in the city.

“Vancouver was a place that had a KKK headquarters and they would parade down Granville Street,” Allen said.

Ultimately, buildings in the neighbourhood were demolished to make way for the Georgia St. Viaduct Replacement Project. Hogan’s Alley became the first and last neighbourhood in Vancouver with a majority Black population.

RECONCILIATION

The City of Vancouver has never apologized for the displacement of the Black community that lived in Hogan’s Alley.

“A public apology is very important,” said Oludolapo Makinde, a graduate student at the University of British Columbia’s Peter A. Allard School of Law.

Makinde is the author of an anti-Black racism strategy for the city: “Towards a Healthy City: Addressing Anti-Black Racism in Vancouver.”

“That community is what is missing and that is what we want to get back,” she said.

The Hogan’s Alley society has also been working with the city to create a land trust proposal, something Stephanie Allen said any municipality should be excited about.

In 2018 the city of Vancouver announced a plan to demolish the viaducts that would include the construction of parks, housing and a community centre -- a plan that would cost $300 million. An agreement was made that year to include an acknowledgment of Hogan’s Alley in an effort to reconnect the community that was displaced.

However, Allen said a draft memorandum of understanding regarding reconciliation was submitted to city council in 2018 but the city has yet to respond.

Nonetheless, Hogan’s Alley Society is continuing to fight for the redevelopment of the small community with a large historic significance.