Newfoundland taught me how to write. Its terrain invites description, its people are vibrant characters, and its stories have classic plotlines: survival, fellowship, scandal and fun.

There must be something about being isolated that incubates all of that. A cross-pollination of creative energy that makes the literature, music, and television produced in or by Newfoundlanders that much better.

And, maybe, it makes anyone visiting better too.

I remember reporting for CTV National News in 1988 when the Calgary Olympic flame was arriving on our most eastern shore, and the story that aired that night was the first time in my then-young career I felt I had written something that was good. Suddenly I was paying attention to syntax, description, and connecting to the viewer through an emotional choice of words. Like Newfoundland itself, my report that night was epic.

Every time I’ve returned to The Rock I have been proud of the story I would tell. At the cusp of 2000 I flew in from New York, this time working for ABC News, to share the story of Harbour Deep.

It was a fishing town on the Northern Peninsula that reaches toward Labrador, which had no way to support itself with the disappearance of cod.

All two hundred residents were asking the Newfoundland government to help them relocate closer to work but the premier at the time, Brian Tobin, was insisting everyone in town had to agree. He knew the political price paid by previous provincial governments for forcing relocation.

Problem was there was one man in Harbour Deep who didn’t want to leave. He was holding up everyone else’s future, and it didn’t seem to bother him at all.

And he was a marvelous character – built dories his whole life and wanted to die building them. In Harbour Deep.

The story aired on an ABC News broadcast that followed the sun around the world as it welcomed the new millennium on Jan. 1, 2000, anchored by the late Peter Jennings in New York.

The 24-hour marathon earned a distinguished Peabody Award for ABC, and our story on Harbour Deep touched on one of the great trends of the 20th Century, the migration of people away from small resource-based towns.

For that same broadcast, Peter and I had convinced ABC News' management to pay for a live location on the main dock in St. John's harbour to share the celebration that was planned around midnight. It was an unlikely choice, and we had to lobby hard for it.

All the other ABC News on-air talent were set up in stunning places like the Eiffel Tower or the Acropolis, fantastic backgrounds devoid of people. My location, standing on a milk carton, stealing light from a CBC friend because ABC hadn't arranged for any, had nothing but people.

They were very drunk and boisterous people dancing and yelling and hugging each other. Peter and his producers loved it, because of all the locations in the world they had planned (more than two dozen), mine was the only one where we were up close to a party.

I got doused with champagne, a buddy tried to get me to down Screech live on air, and my family (whom I had brought with me for the celebration) acted as the security to ensure the live links didn't get unplugged by revelers.

They kept coming back to me (Peter also had a soft spot for Newfoundland) and eventually I ran out of things to say so I asked the cameraman to shoot the band that was performing on stage.

We hadn't paid for the rights to broadcast the music but we did it anyway because the songs were so infectious. I was already a fan of Great Big Sea, I listened to them often to remind me of home when I crossed the George Washington Bridge into Manhattan every morning, so I knew a fair bit about them.

To the 175 million Americans watching that night, I told them about the Celtic rock fusion movement that GBS was leading, the history of its lead singer Alan Doyle having grown up in a fishing village, and shared the enthusiastic foot stomping that was shaking the pylons the doc was built on.

It was a marvelous party and I have to believe the exposure the band received that night helped them become the international success they were.

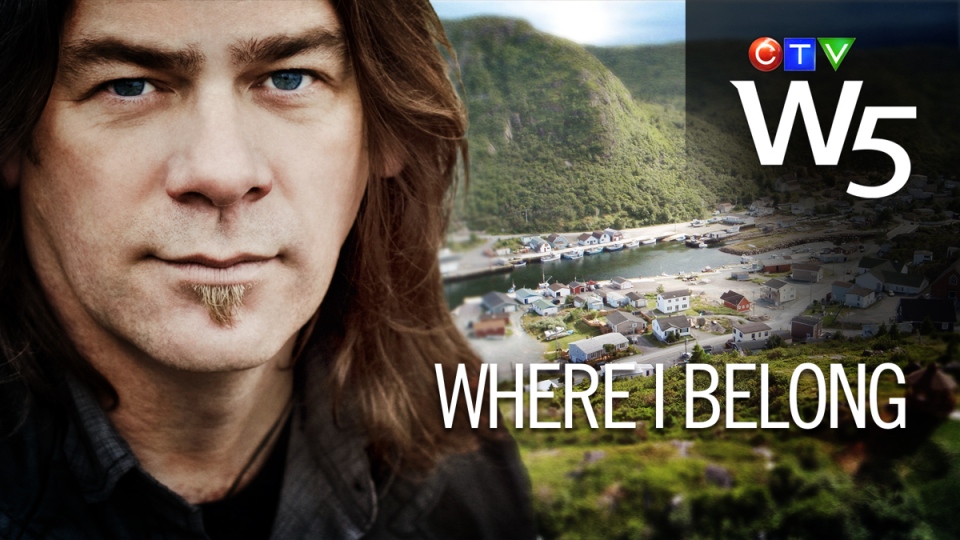

For this episode of W5, I returned again to Newfoundland to finally meet Doyle face-to-face. When our producer Mary Dartis and I arrived in St. John’s, there was a message waiting for us to join Alan and his wife for dinner.

Normally, we would be reluctant to accept a social invitation from someone we’re about to cover, but every previous visit to the island began the same way (I’ve been invited to two taxi drivers' homes for the same thing) so we agreed to go.

Doyle and his wife and son were gracious hosts, but I had trouble connecting with him at first. He’s a bundle of energy, like the fidgety kid in class who drives the teacher crazy, flirty and ready with hilarious one-liners. His song lyrics betray a sensitive and thoughtful soul, so I knew we’d have a good interview eventually. He just needed to entertain us first, which he did.

A few days later, Doyle’s demeanor grew softer as we approached the fishing village he was born and raised in, Petty Harbour. It’s the place he writes passionately about in his autobiography 'Where I Belong.'

Sitting on rocks with the ocean around us, and a rare clear blue sky overhead, we talk about the recent breakup of Great Big Sea, his solo career, and how his family and friends shaped him.

Then we move to what is believed to be the oldest standing Irish-style cottage in Newfoundland and continue our conversation, sharing his insecurities, regrets, and the special professional relationship he has with Oscar-winner Russell Crowe.

Crowe has collaborated on some of Doyle’s songs, and Doyle has appeared as the Merry Men’s minstrel in the movie Crowe starred in, Robin Hood. It’s clear the two men share a strong bond.

After we completed our filming and began to return home, I was reminded of another thing that seems to happen whenever I visit Newfoundland: airplane problems. The landing gear wouldn’t retract so we circled out in the ocean to dump the aircraft’s excess fuel, and landed safely back at the airport, fire engines chasing us along the runway just in case.

It’s the third time in Newfoundland (and the only place) I’ve found myself wondering how a flight was going to turn out. A sensible person might see an omen and not risk a return visit.

But I will always be drawn to Newfoundland and its island of storytellers, and the growing number of people I consider friends who never fail to make me feel welcome with a scoff and a scuff (look it up if you don’t know).