After a long, cold winter led to massive die-offs of honey bees in Canada, a group of B.C.-based beekeepers is aiming to stave off future losses by breeding genetically superior honey bees.

Iain Glass, a honey bee geneticist, is working with local beekeepers in Vancouver Island to breed bees with genetic traits that would make them well-suited to survive what he says is a perfect storm of threats to colonies across Canada: a warming world, modern agricultural practices, relocation stress and attacks from pests such as the parasitic Varroa mite.

“The more normal thing with bees has been to medicate to try to deal with stress, rather than saying, ‘Let’s isolate various genetic traits,’” Glass told CTV’s Your Morning on Monday.

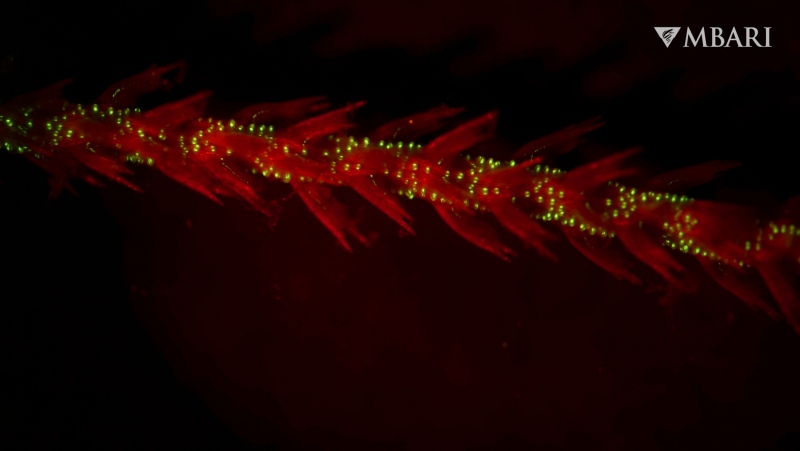

Some of those traits are what beekeepers and researchers describe as “hygienic.” They allow honey bees to remove dead and diseased larvae from the part of the hive where the queen bee lays eggs, which prevents disease from spreading.

The “grooming” trait is also in-demand for strong bee colonies. That feature allows bees to spot and kill mites that attack other bees.

“The Varroa mite biting you allows opportunity for infection,” Glass said.

He and his colleagues breed superior bee colonies through a technique known as “reproductive isolation.” They bring a hive of drone bees with highly valuable genes and a group of queen bees ready to mate to a remote area where no other bees are kept.

“It’s basically animal husbandry,” Glass said, adding that it would take at least four years before a full colony of “adaptive” bees could be bred.

Since a typical queen bee can breed with anywhere from five to 20 drones, there will be a lot of genetic variation among the bees in the colony, allowing scientists to track and maintain specific traits from the hive.

Honey bees are responsible for pollinating many of the fruits and vegetables that humans and animals consume. According to Statistics Canada harvest data from 2016, honey bee pollination contributes as much as $5.5 billion in additional crop value to the economy.

But bees are in trouble across Canada.

In 2018, the overall reported colony loss in the country was the highest it has been since 2009, according to an annual survey from the Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists. Ontario beekeepers reported “astounding” losses this past winter. And in B.C., where Glass works, chronic bee shortages have left beekeepers no choice but to import thousands of bees from California, Hawaii and even New Zealand.

Last week, Health Canada announced a phasing out of the use of neonicotinoid pesticides, which beekeepers and scientists say make bees more vulnerable to viruses, parasites and loss of food supplies.