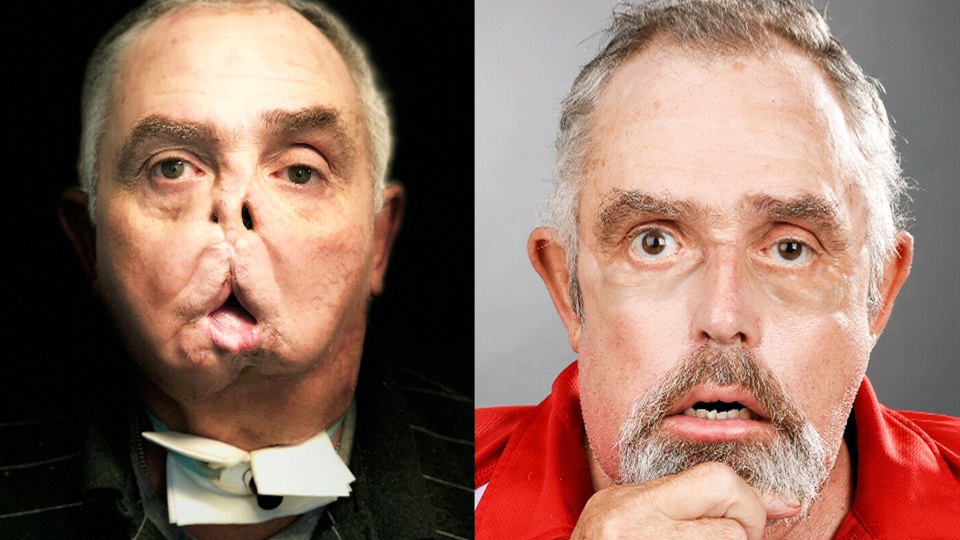

Seven years ago, Maurice Desjardins lost his nose, lips, teeth and upper and lower jaws when he was accidentally struck by a bullet from a hunting rifle. In the years that followed, surgeons were never able to fully rebuild his face.

“This guy didn’t have nose or lips. He didn’t have an upper jaw, lower jaw; he couldn’t speak couldn’t swallow and couldn’t breathe properly,” plastic surgeon Dr. Daniel Borsuk told CTV’s Your Morning on Monday.

But four months ago, that all changed. That’s when the Montreal surgeon successfully performed the first face transplant in Canada, after spending six years planning for the historic surgery.

Dr. Borsuk says his team at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital in Montreal wanted to give Desjardins the simple abilities to speak, eat and sleep.

“Basically everything that you or I take for granted, that’s what we wanted to give him.”

Before the surgery, Desjardins’ life was one of constant pain from the scar tissue and the damaged nerves in his face. Before Borsuk, surgeons who operated on Desjardins had used bone chiseled from his fibula—a bone in the calf—to try to reconstruct his face. But he was still left with two holes where his nose used to be and a puckered mouth that he couldn’t close, which meant he was constantly drooling and couldn’t eat.

Borsuk wants everyone to know that Canada can offer “gold-standard treatment” to patients looking for major facial reconstruction.

“I think a lot of the times we see Canadians that say ‘maybe there’s a better option outside the country,’” he said. “And it’s nice to offer gold-standard treatment to all of our entire population.”

“We have fantastic surgeons, great medical and health system and it’s nice that we’re finally able to offer this type of procedure to anyone.”

His patient, Desjardins, had spent years breathing through a tracheostomy—a tube inserted into a hole in his windpipe that he used to breathe. The team wanted to give him the ability to breathe on his own.

“We wanted him to look normal. We wanted him to walk around in public without anyone look at him,” he said. “And for his wife to sleep able next to him without those awful sounds coming out of his tracheostomy.”

But Desjardins still has a long road to recovery.

“It’s only been four months, and he still doesn’t have the use of his lips,” Borsuk said. “He’s starting to smile. He’s starting to eat and drink better but it’ll probably be another six months before he’s smiling.”

Dr. Daniel Borsuk was the lead surgeon who performed Canada's first face transplant surgery earlier this year and says it'll be "be another six months before he’s smiling."

But part of that recovery actually started well before the surgery. For two years, Desjardins was regularly evaluated by psychiatrists.

“It’s not just transplanting an organ, you’re transplanting a lot more,” Borsuk said. “We communicate with our faces, so when you’re transplanting this you want to make sure that the recipient is able to deal with what’s going to happen having this new face.”

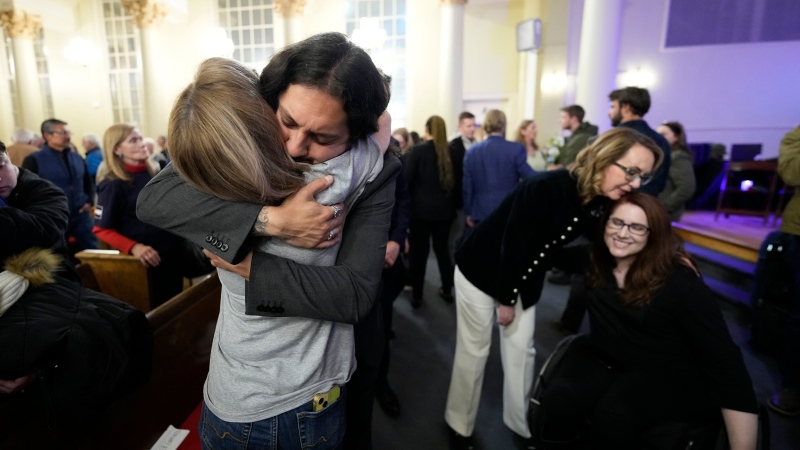

Borsuk is reluctant to take praise for the groundbreaking surgery and was more inclined to call the donor and their family “the true heroes.”

“Can you imagine on the worst day of your life when you lose a loved one and you’re approached for organ donation and this family gives all the organs of his loved one—including the face?” Borsuk said.

“It’s the most harrowing day of their life and they’re going ahead and probably giving the most generous gift you can give to another person. It’s unbelievable. So they’re the true heroes.”

For the Montreal surgeon, his most recent success was the result of years of experience which began back in 2012. Then, he was a fellow at the University of Maryland and a part of the surgical team who performed a pivotal face transplant surgery in Baltimore, Md.

In that case, Borsuk sheared away the scar tissue of the recipient, a 1997 gunshot victim, and prepared the face of a 21-year-old brain dead organ donor.

Since then, he’s used his skills for facial reconstruction and worked with children with cancer or burns scars; mutilated pitbull attack victims and children born with so-called “elephant man” disease or neurofibromatosis—a genetic disease which gives them deformed bones, malformed skulls and jaws.