TORONTO -- The chances that a made-in-Canada experimental Ebola vaccine will successfully make its way through the developmental pipeline and into use in West Africa improved dramatically Monday with new high-powered help taking over the project.

Pharma giant Merck, which has nearly a century's worth of vaccine production experience, has acquired the licence to produce the experimental Ebola vaccine from a small U.S. biotech, NewLink Genetics.

The deal gives the vaccine the guidance of a team that knows how to shepherd products through testing and the regulatory process, as well as access to in-house expertise in producing live virus vaccines, like the Canadian Ebola product.

"We will be taking primary responsibility for advancing this program. And our intent is to do everything we can to make things happen as quickly as possible and be able to bring them to scale as quickly as possible to not only evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of this vaccine, but if it is shown to be promising in those regards to make sure that it can be as widely available as quickly as possible to as many people who could benefit from it," Dr. Mark Feinberg, chief public health officer for Merck Vaccines, told The Canadian Press in an interview.

The deal earns NewLink, of Ames, Iowa, a substantial payday. The company, which paid $205,000 for the licence for the Ebola vaccine, will get US$30 million up front, an additional US$20 million when the vaccine goes into efficacy testing and royalties if and when the vaccine is approved and sales begin. There will not be royalties paid, though, on doses of the vaccine that are sold to African and other low-income nations, Feinberg said.

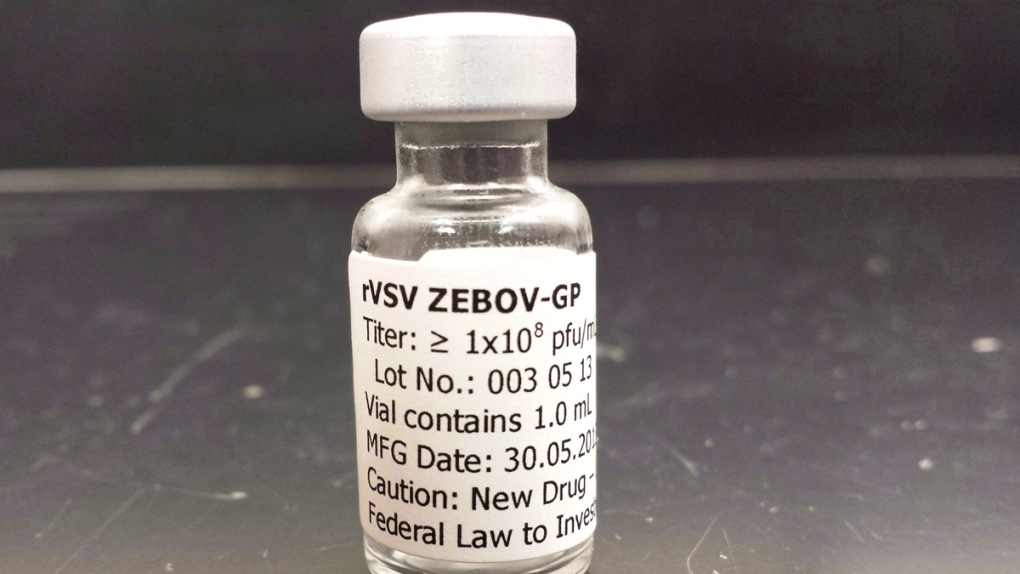

The vaccine, called rVSV-EBOV, was designed by scientists at Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. The deal is worldwide and exclusive and covers other vaccines created by the Winnipeg lab using the same delivery method. That means as a result of this deal Merck could develop a Marburg virus vaccine, as well as one against Lassa, another viral hemorrhagic fever virus.

As well, the company could develop vaccines against other strains of Ebola. The vaccine currently in testing protects only against the Ebola Zaire strain, the one responsible for the current West African outbreak. Or it could produce a multi-valent Ebola vaccine, one shot that protects against the main strains that cause human disease.

NewLink acquired the licence for the Canadian vaccine in 2010. At the time, there was no interest among Big Pharma players to develop Ebola vaccines, which may explain why the company was chosen and why the licensing fee was so low. The federal government has not explained how the $205,000 fee was reached.

Ebola vaccines are unlikely to be money makers. The outbreaks happen sporadically and -- before this one -- in small numbers. The largest outbreak before this year involved 425 people. And outbreaks happen in countries that are among the poorest in the world, with the least capacity to pay per-dose prices that would cover the cost of development.

Some costs will likely be recouped by sales to countries like the United States, which may want to stockpile Ebola vaccine against perceived bioterror threats.

"We do not see this as a commercial opportunity and that is not what's driving our engagement," Feinberg said when asked why Merck is taking on this project.

"Our legacy in bringing about breakthrough medicines and vaccines in major disease areas such as HIV, hepatitis and human papillomavirus calls us to intervene and work with partners to find solutions that will address this new global public health crisis," said Chirfi Guindo, president and managing director of Merck in Canada.

The deal was welcomed by the World Health Organization, which is leading a push to fast-track experimental Ebola vaccines for use in West Africa.

"It's good news," said Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, the assistant deputy director who is spearheading the Ebola vaccine and drugs effort. "We have now to see how this will work with Merck online, but I am confident that it will be fine."

Monday's announcement culminated weeks of negotiations between the two companies and will be greeted with enthusiasm by parties hoping the vaccine can be used to contain the ongoing Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

There had been widespread concern that NewLink did not have the muscle or the experience to get the vaccine through testing and into use. The biotech does not have its own vaccine production facilities and has not yet brought a product through licensure and to market.

But in partnering with Merck on the Ebola vaccine, it has gained what it did not have. A multinational with operations in 140 countries, Merck is a major player in vaccine production.

In particular, Merck has substantial experience in the manufacture of live-virus vaccines grown in vero cells. The Canadian Ebola vaccine is a live virus vaccine grown in that production substrate.

"Merck is committed to applying our vaccine expertise to address important global health needs and, through our collaboration with NewLink, we hope to advance the public health response to this urgent international health priority," Dr. Julie Gerberding, president of Merck Vaccines, said in a statement.

The vaccine is one of the two most advanced Ebola vaccines currently in play. And of the two, it is the one scientists believe has the better chance of working in West Africa.

It is thought the vaccine should be able to protect with a single dose, which is critical in countries where health-care systems are in tatters. As well, testing in non-human primates suggests it may work both as a standard vaccine -- given to healthy people to prevent infection -- and as a post-exposure treatment for people newly exposed to the virus.

There is no evidence to suggest the other vaccine, made by GSK (formerly GlaxoSmithKline), could be used as a post-exposure treatment.

The GSK vaccine is further along in testing. But it is feared that vaccine will require two doses -- a priming dose and a boosting dose, perhaps with a different vaccine. The would be hugely challenging to deliver in the outbreak countries.

Under the agreement, the Public Health Agency of Canada retains non-commercial rights pertaining to the product.

"This vaccine is the result of years of hard work and innovation by Canadian scientists," Health Minister Rona Ambrose said in the statement.

"We are pleased that this new alliance coupled with the clinical trials currently underway will further strengthen the possibility that the vaccine will make a difference in the global response to the Ebola outbreak."