Vancouver police are trying to reassure the public that they are working harder to keep all women safe a day after the missing women’s inquiry released a damning report criticizing police for not stopping serial killer Robert Pickton sooner.

“On behalf of the Vancouver police Department I would again like to say we are sorry to the families and friends of the missing and murdered women. We could have and we should have caught Pickton sooner,” said Vancouver Police Chief Const. Jim Chu, speaking at a news conference Tuesday morning. “We are in the process of studying Commissioner Oppal’s findings. We have also conducted a detailed internal review and we’re committing as police officers to do everything we can to make sure a tragedy like this doesn’t happen again.”

Chu detailed various steps his force is taking to be more responsive. He said Vancouver police are working closely with the Integrated Homicide Investigation Team responsible for looking into murders in the Lower Mainland areas and are now proactively engaging with sex workers in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

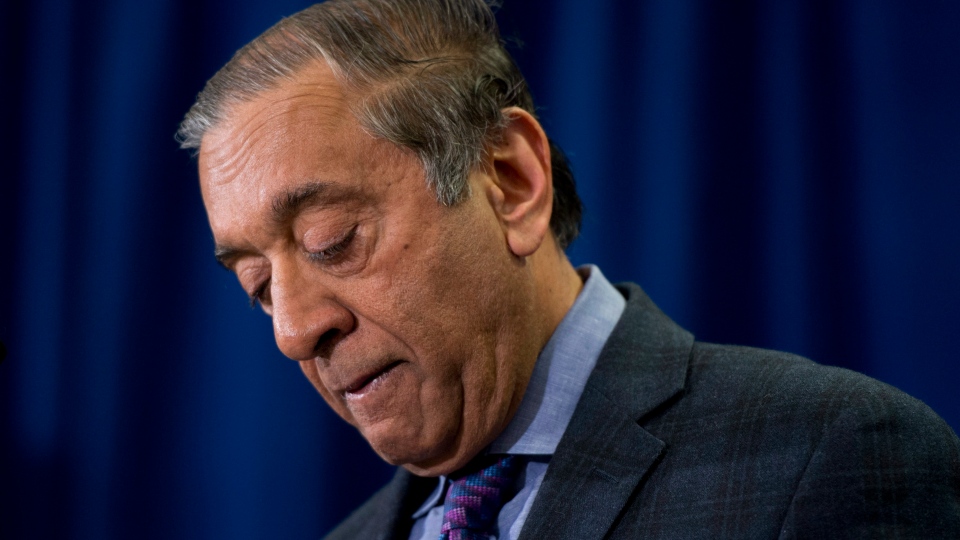

Commissioner Wally Oppal released Monday his final 1,448-page report on how Vancouver police and the RCMP responded to reports of women missing from the notorious Vancouver neighbourhood, finding that Pickton got away with murdering so many women due to “systematic bias” against the former pig farmer’s poor, aboriginal, drug-addicted victims.

Oppal also issued a list of recommendations on how to better protect at-risk women in the future.

The commissioner said Tuesday he’s encouraged by the steps being taken by police and that he has faith in both Chu and Const. Linda Malcolm, the sex-industry liaison for Vancouver police.

“I’m very encouraged and positive about what they said,” Oppal told CTV News Channel. “There has to be a closer relationship between people in the Downtown Eastside who feel disaffected and Vancouver police. We need real community policing.”

Oppal said the city as a whole had displayed indifference toward the missing women because of their low status, with news of their disappearances only coming to light through media reports.

“Had the women come from the more affluent areas, like (Vancouver’s) west side, I doubt very much there would have been as much indifference,” Oppal said.

Pickton was eventually convicted of six counts of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in one of Canada’s most notorious criminal cases. The DNA of 33 women was found on his farm, and he once told an undercover police officer he killed 49 women.

Pickton was arrested in February 2002, but Oppal’s report called out how there was evidence from as early as 1991 to indicate that a serial killer may be on the loose.

Findings from the missing women’s inquiry

Oppal's report -- titled "Forsaken" -- was based on a public inquiry that heard from 80 witnesses, including police, Crown prosecutors, sex workers, academics and the families of missing women.

The report includes a total of 63 recommendations on protecting at-risk women, from providing more funding to centres for sex workers, to establishing better public transit options between northern communities and appointing two advisors to consult with those affected by Pickton's crimes.

Oppal also recommended setting up a compensation fund for the children of the missing and murdered women and establishing a healing fund for victims’ families.

The report had examined the role played by police in the missing women investigations, identifying poor report-taking and a distrustful relationship between police and sex workers as issues that contributed to the tragedy.

Chu issued a statement Monday saying the force has already taken measures to ensure the same errors are not repeated, including completely overhauling the missing-persons unit and its outreach programs.

"We know that nothing can ever truly heal the wounds of grief and loss but, if we can, we want to assure the families that the Vancouver Police Department deeply regrets anything we did that may have delayed the eventual solving of these murders."

Deputy Commissioner Craig Callens, commanding officer of the B.C. RCMP, also re-stated his force's regret at the deaths, but stopped short of admitting any wrongdoing.

He said the RCMP is still digesting the report and declined to take questions.

"Policing is constantly evolving, and on an ongoing basis, it is necessary for us to look critically at how we deliver policing services to ensure that we respond effectively to our community's needs and expectations," he said.

Critics of the process have steadfastly maintained they disagree with the inquiry's composition and its limited terms of reference. They have complained about the province's unwillingness to pay for lawyers to represent sex-trade workers and aboriginal women's groups during the inquiry, which stretched eight months.

Those critics have called for a national public inquiry into the hundreds of murders and disappearances of aboriginal women and girls across the country. Oppal's report did little to quell those demands, which have been echoed by the Assembly of First Nations, Human Rights Watch and Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson.

Victim’s families react

In the meantime, the sister of one of Pickton's victims said she’s relieved she can finally close a long chapter in her life, following the release of the report.

"I'm really glad it's all over because it took its toll on so many of us family members. And it's like a big weight has been lifted off my shoulders," said Sandra Gagnon, whose sister Janet Henry was killed by Pickton. "I want to put this behind me and start living again."

Gagnon said Tuesday she was impressed by Oppal's report.

"All I can say is I'm really relieved with what Wally Oppal has done and what he has said about the women. He was really compassionate about the women and about getting help," Gagnon told CTV's Canada AM.

She added: "I found him to be very adamant about doing what we can about the women who went missing and how he wants Vancouver police to handle cases. And also to have more compassion for the women who went missing from the Downtown Eastside.

"I've said so many times during my interviews: if they were women from anywhere else, more would have been done. But because the women were missing from the Downtown Eastside … they didn't do anything about the missing women in the beginning. And in the end there were so many women that went missing, including my sister."